Field Research 2016-2019

Beta maṣāḥǝft working papers 1

After Ethio-SPaRe: Beta maṣāḥǝft Field Research

Part 1: Further churches of Tigray and their manuscript collections

Mission report: read online or download PDF file.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.25592/uhhfdm.13984

Public Report

ʾƎnqwaqo ʾƎnda Maryam Däbrä Mongway

Zǝqallay Mädḫane ʿAläm Bäräkti, Zǝqallay ʾOm Ṣällim Sǝllaśe

May Läbay Däbrä Mäwiʾ Qǝddus Minas

Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Däbrä Ṣäḥay Qǝddus Gäbrǝʾel

Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam

After the termination of the project Ethio-SPaRe in May 2015 it was still possible to make a few field research trips to Ethiopia, Tigray, using the remaining overheads and cooperation links, in particular with the project Beta maṣāḥǝft: Manuscripts of Ethiopia and Eritrea, to wrap up some activities and evaluate prospects of the continuation of work. The trips took place in September 2016, September 2018, and March 2019[1]. The report contains information on nine ecclesiastic institutions. The situation that I encountered in the area of research was much less conducive to the presence of non-Ethiopian researchers than in 2010–2015, and the field research endeavours resulted in successes of various degrees. Hopes to continue reconnaissance after March 2019 were dashed by the deteriorating political situation and the growing tension between the Government of Tigray and the Federal Government of Ethiopia, the pandemic, and finally by the outbreak of the dramatic Tigray war in November 2020. The conflict formally ended with a peace agreement between the warrying parties in November 2022, but it caused a great loss of life, sufferings and irreparable cultural losses. I find it extremely important to keep gathering in a systematic way the information about the ecclesiastic sites and manuscript collections of northern Ethiopia, especially in the time when the need for their study and recording will be unlikely addressed in view of other formidable challenges, for several years at least. As before, I publish the report in the confidence that, unless seen by specialists, recorded and digitized, and in the best case made known through studies, the cultural riches are highly endangered. Their damage and disappearance due to any reason will be hardly noticed even under normal conditions, not to say during a time of military confrontations or natural calamities. Besides, the report below is meant to contribute to the study of ecclesiastic landscape of northern Ethiopia and its manuscript collections, known still by far not sufficiently enough, and from time to time surprising the researchers[2].

ʾƎnqwaqo ʾƎnda Maryam Däbrä Mongway

Fig. 1. ʾƎnda Maryam ʾƎnqwaqo. General view

The church ʾƎnqwaqo ʾƎnda Maryam (Däbrä Mongway) is located in wäräda Naʿǝder ʿAdet (Central Təgray), ṭabiya Ğǝra, just a few kilometers from the town of Səmäma. To reach the church, one has to leave the flat highland and descend to a lowland area covered with thick vegetation. The foundation is of däbr-status, said to have have been served by nearly 100 priests and deacons at the moment of the visit. The round church building stands hidden between the trees (fig. 1); it could not be older than the second half of the 19th or the 20th century. It was in the process of reconstruction in the time of the visit, an additional wall was erected around to expand the old structure. Inside, the rectangular mäqdäs (sanctuary) was covered with murals (figs 2, 3). It was not possible to collect any specific information on the foundation of the church, except statements that it was founded long ago “by the local people”.

Fig. 2. ʾƎnda Maryam ʾƎnqwaqo. Painting on a side of the mäqdäs (sanctuary).

Fig. 3. ʾƎnda Maryam ʾƎnqwaqo. The church inside.

The manuscript collection turned out to encompass at least 30 books or more[3], of different ages, quite interesting, but partly in a very bad state and kept in extremely poor conditions. Placed in a big old wooden chest behind the mäqdäs together with many other objects, in great disorder, many of the manuscripts were badly damaged, the older ones laying on the bottom of the chest. There was at least one plastic bag with fragments and destroyed manuscripts.

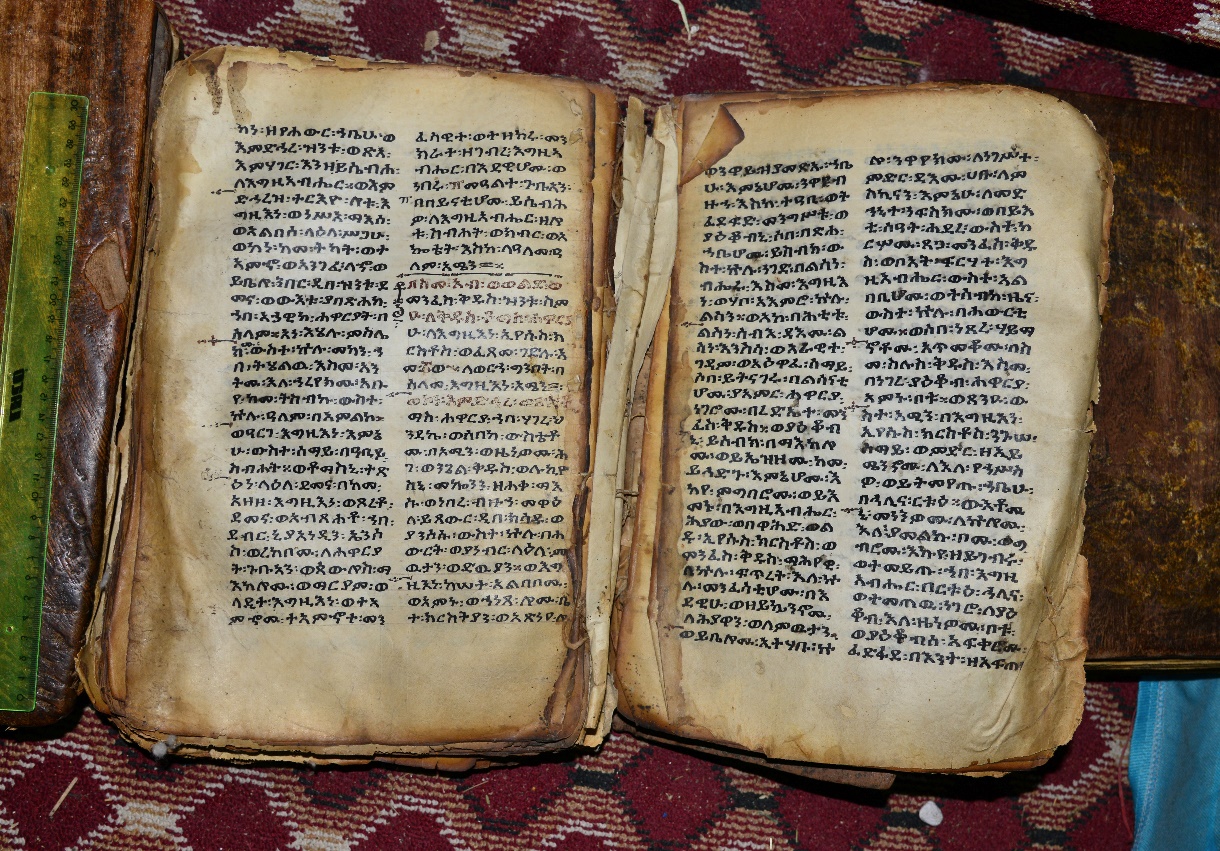

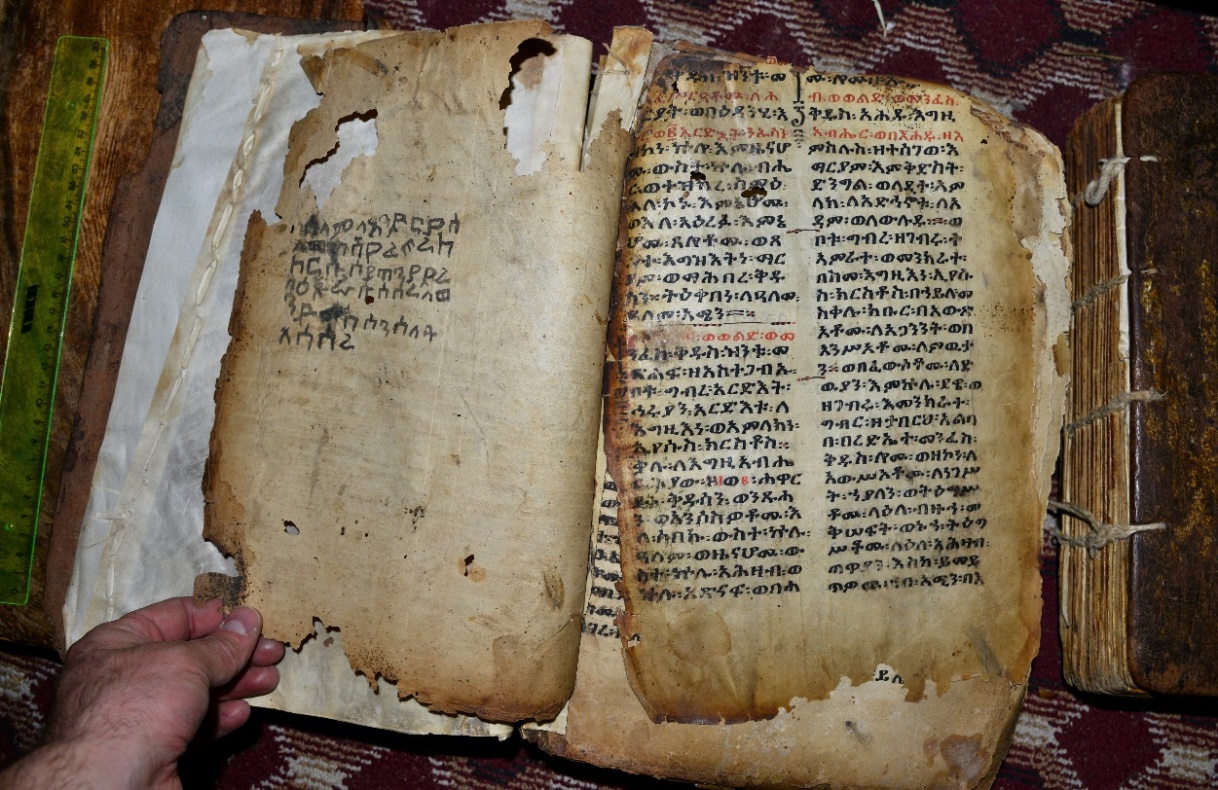

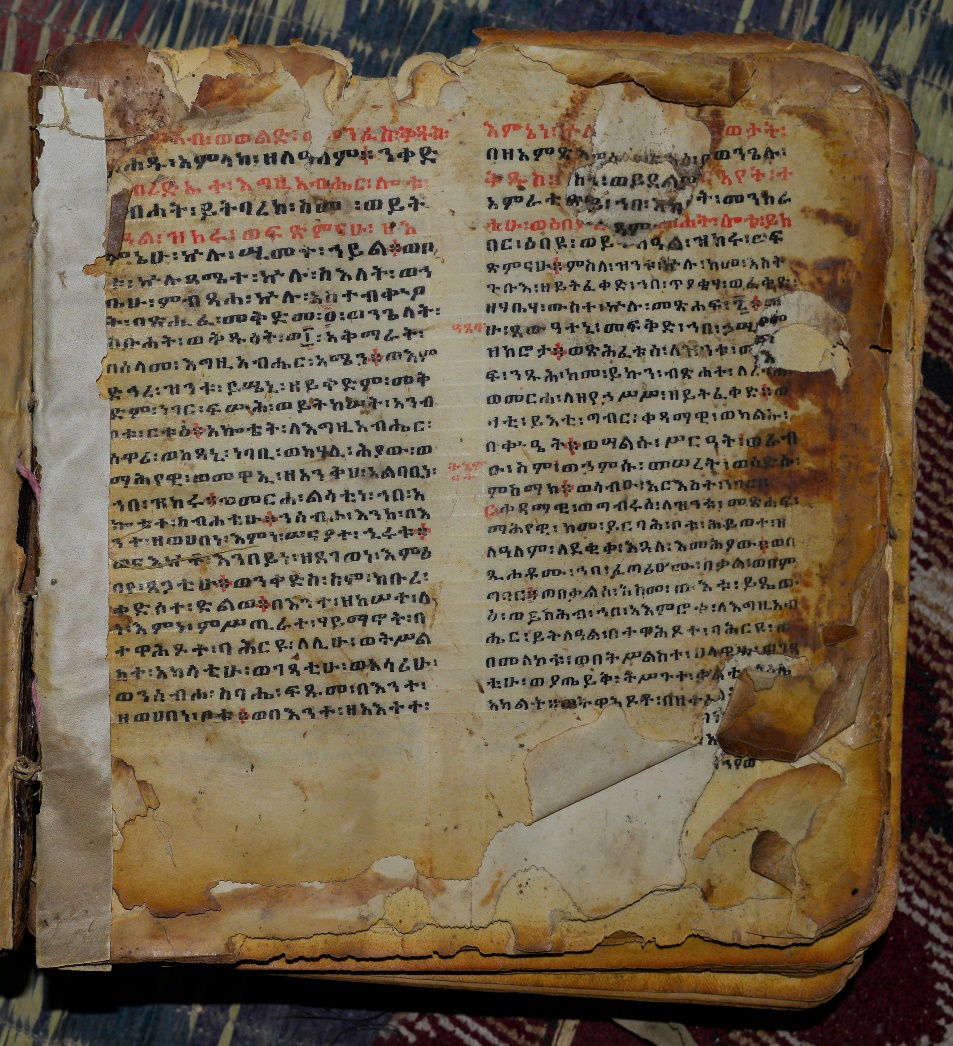

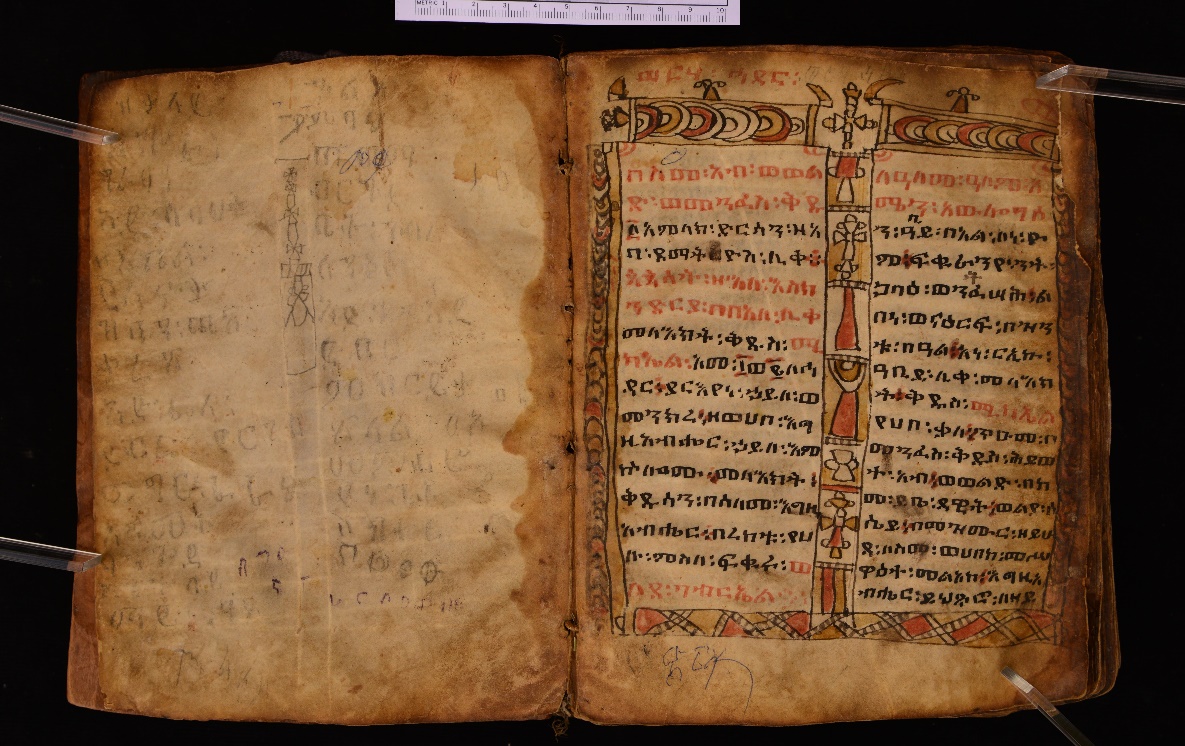

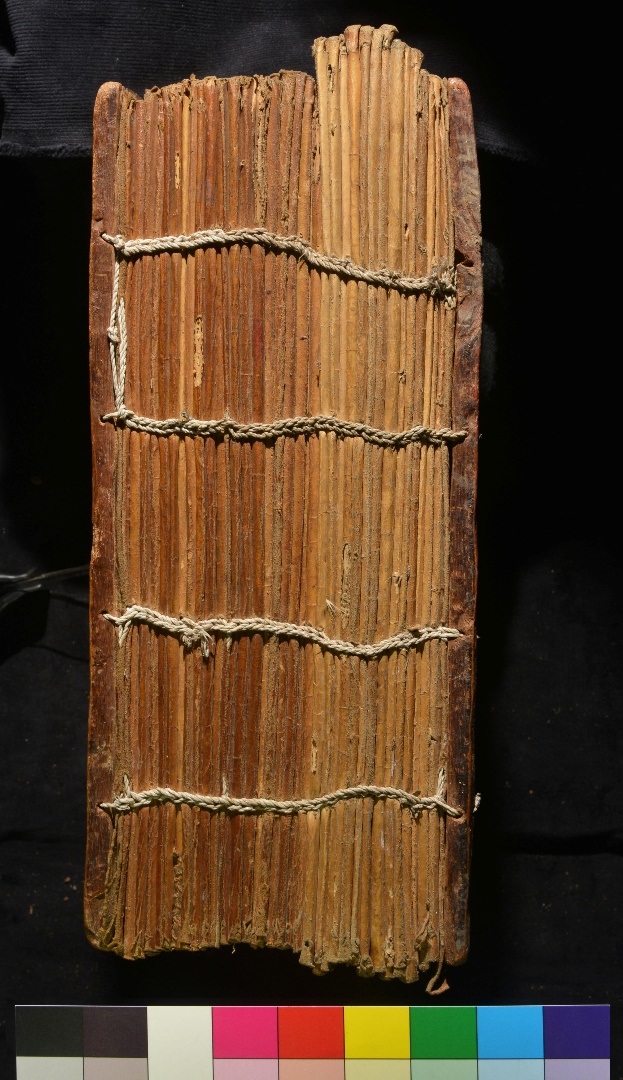

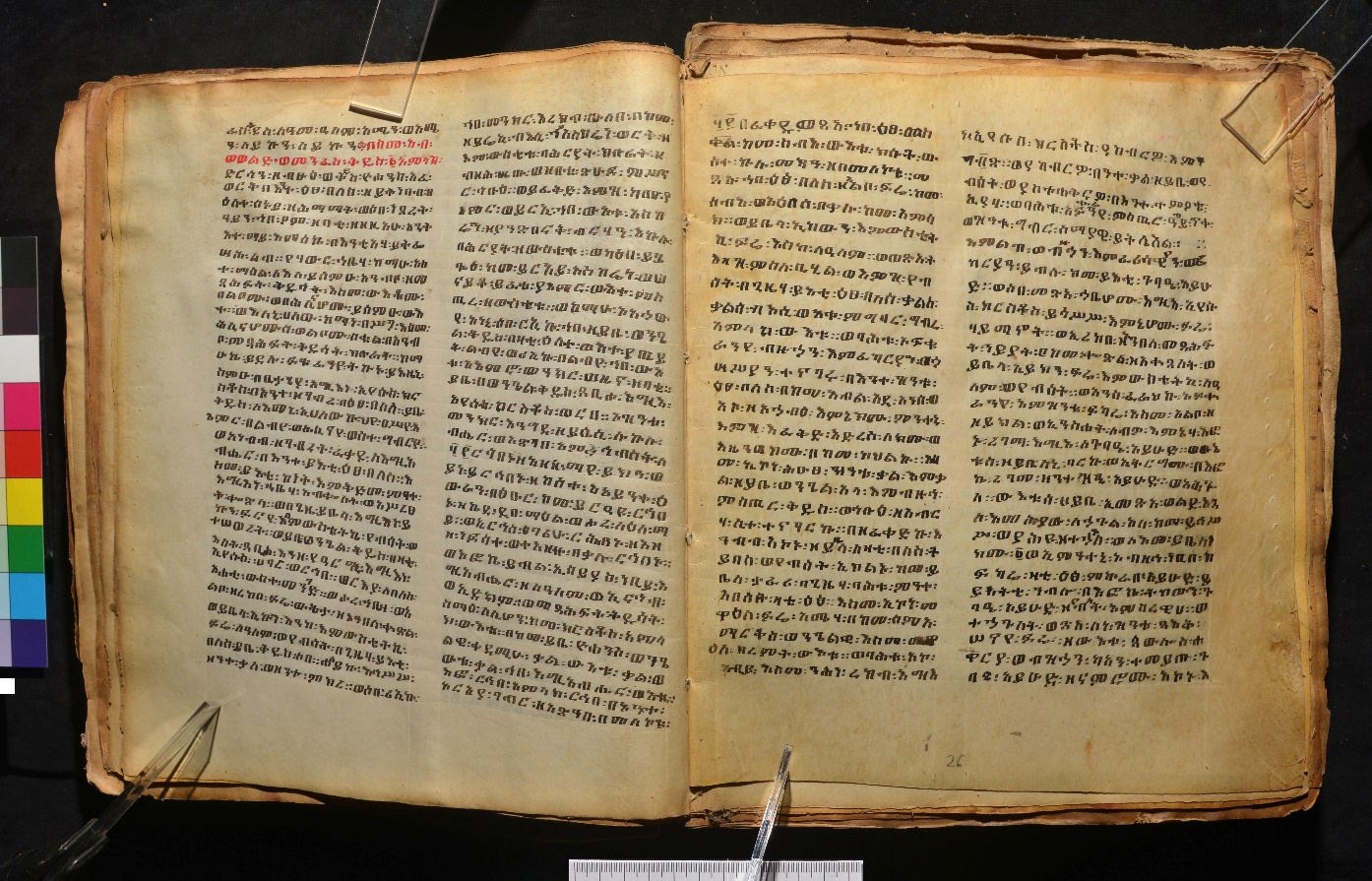

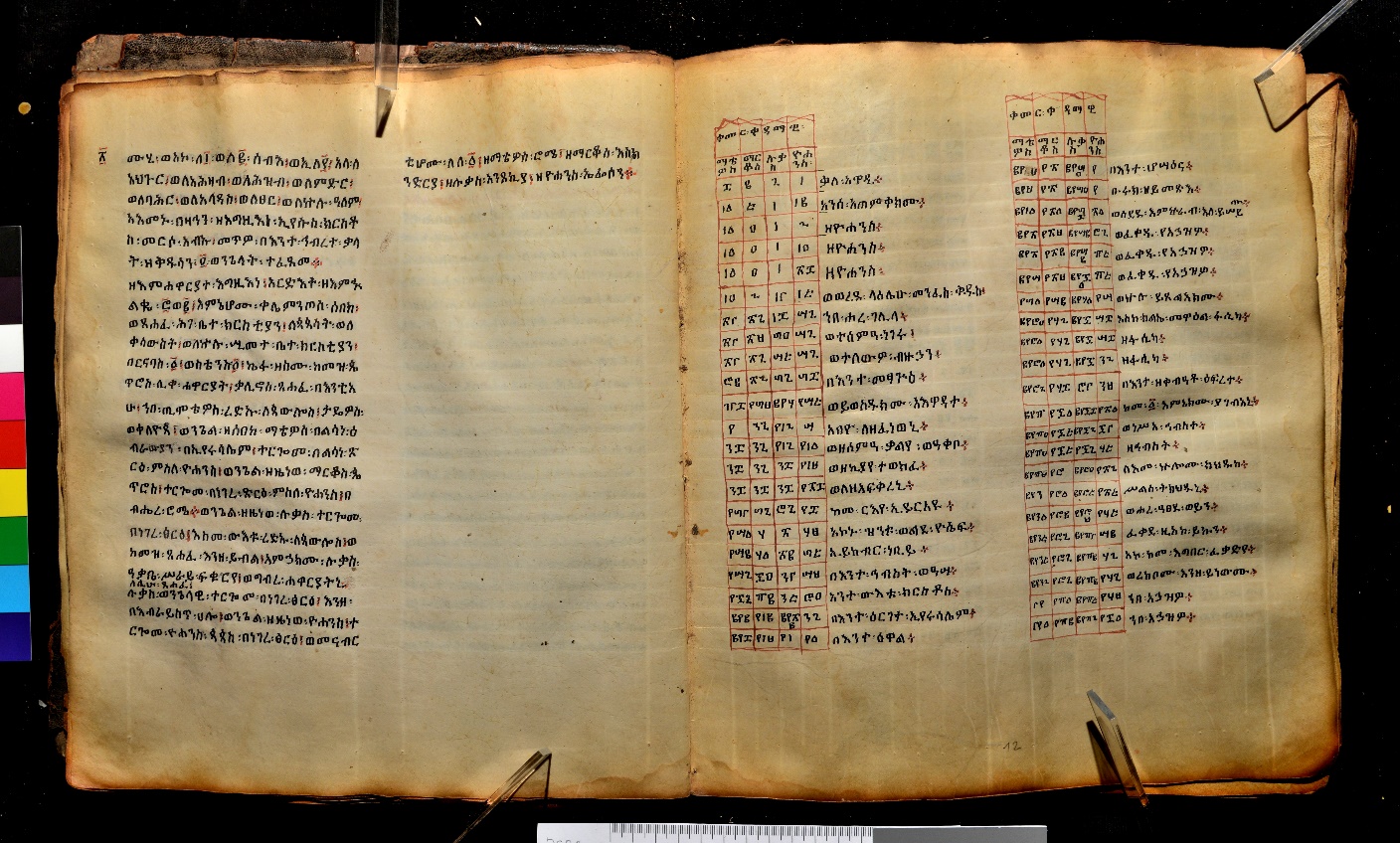

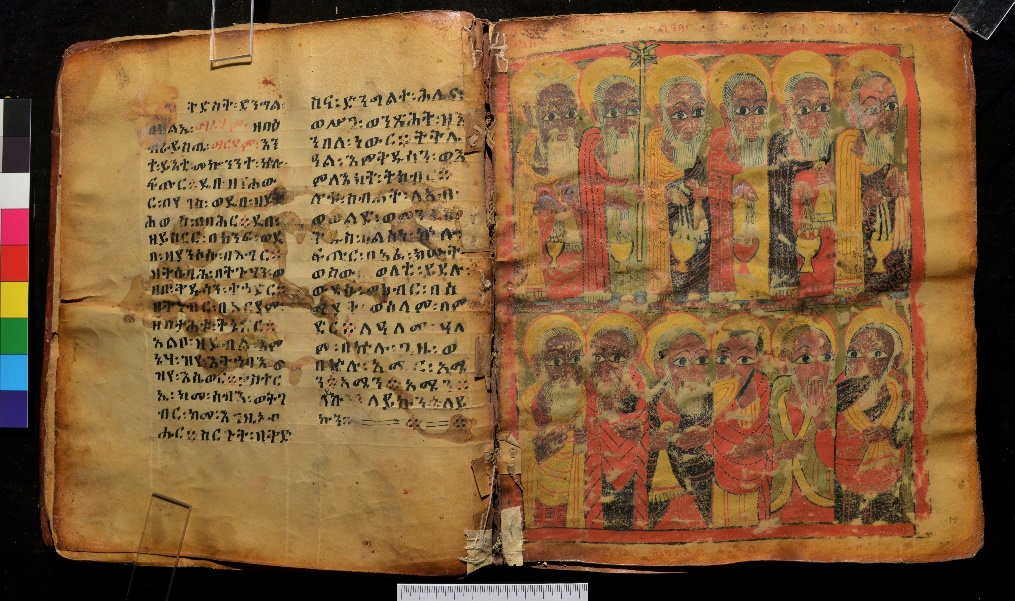

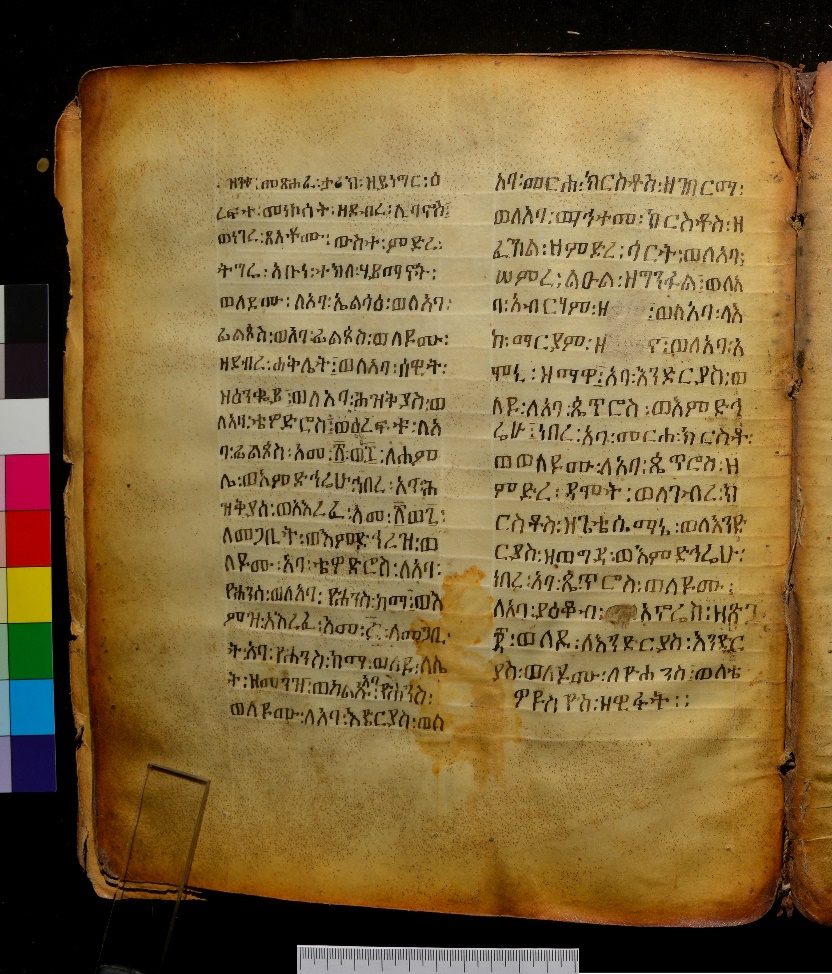

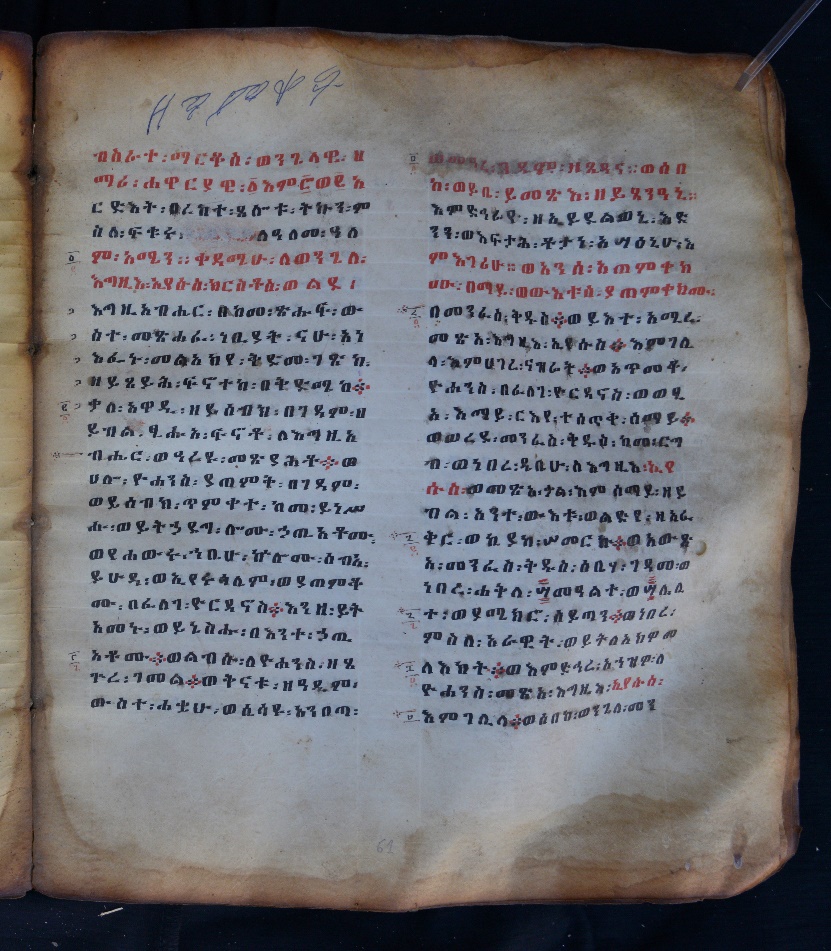

The most remarkable item of the library is a sizable volume of the Apocryphal Acts of the Apostles, dating to the second half of the 14th/ first half of the 15th century (figs 4, 5). It contains also a poorly understandable late 16th-/early 17th-document in Geez possibly telling about a legal procedure concerning a rəst-land (figs 6, 7). The manuscript was in poor condition; the leaves were in complete disorder, placed between the two thick wooden boards of the binding (fig. 8).

Fig. 4. ʾƎnda Maryam ʾƎnqwaqo. Apocryphal Acts of the Apostles, second half of the 14th/ first half of the 15th century.

Fig. 5. ʾƎnda Maryam ʾƎnqwaqo. Apocryphal Acts of the Apostles, second half of the 14th/ first half of the 15th century, incipit on the recto-side, protective text on the verso-side.

Fig. 6. ʾƎnda Maryam ʾƎnqwaqo. A later document in the Apocryphal Acts of the Apostles.

Fig. 7. ʾƎnda Maryam ʾƎnqwaqo. A later document in the Apocryphal Acts of the Apostles.

Fig. 8. ʾƎnda Maryam ʾƎnqwaqo. Apocryphal Acts of the Apostles, second half of the 14th/ first half of the 15th century. The upper board of the binding.

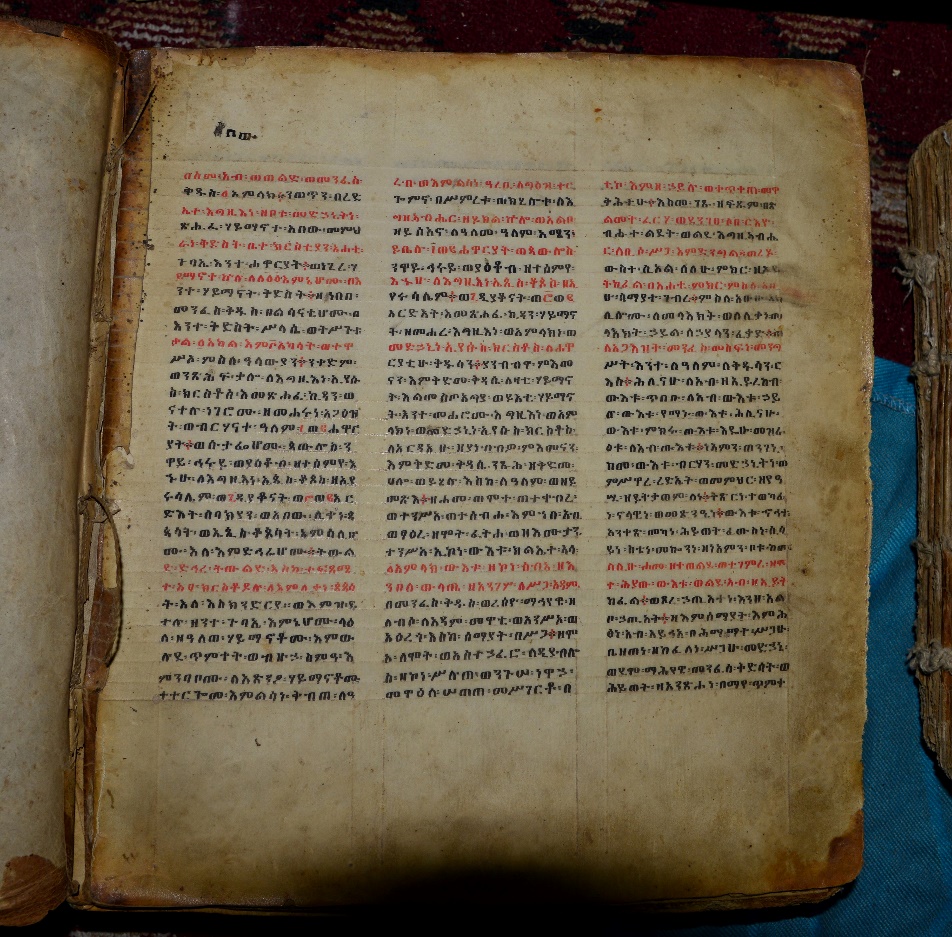

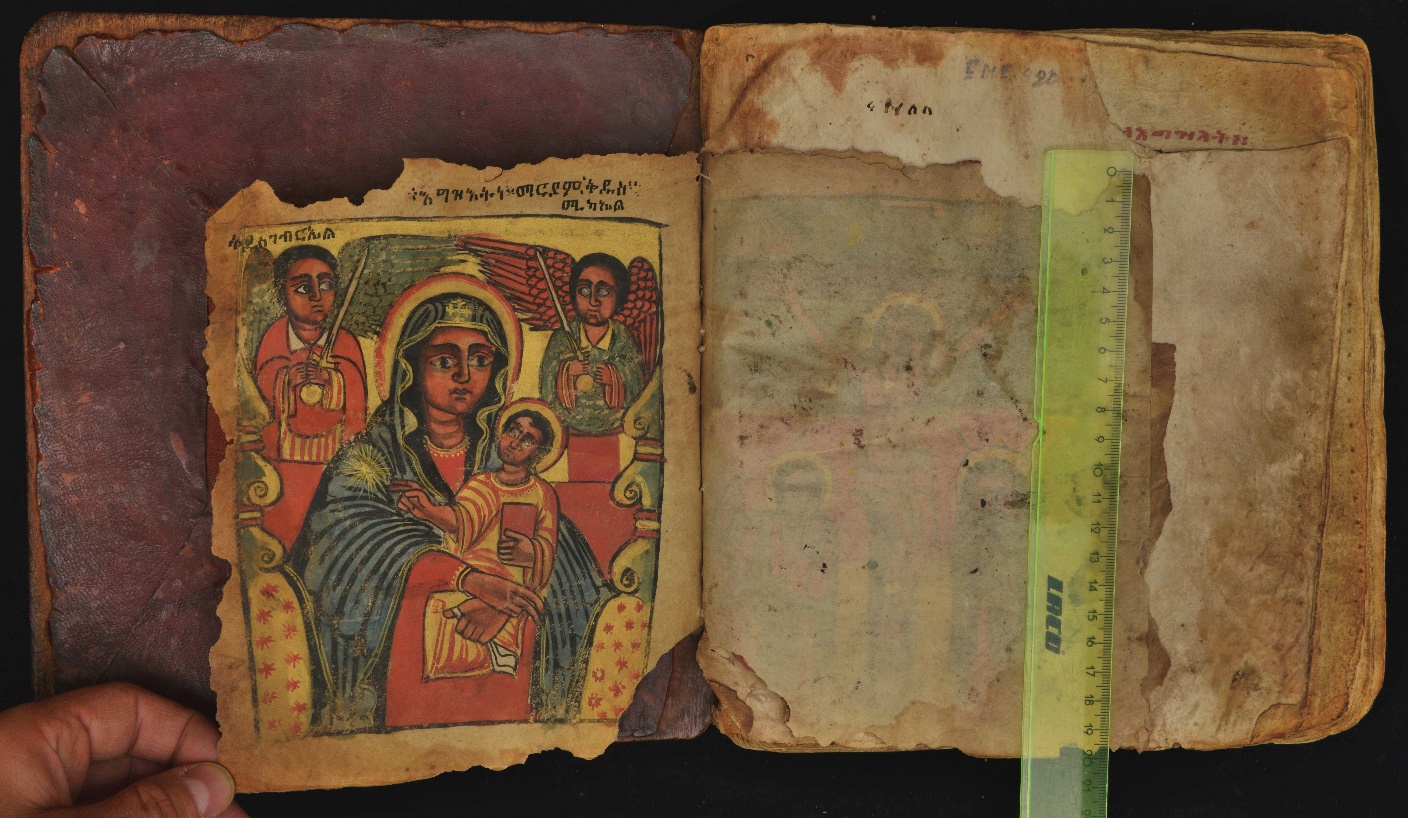

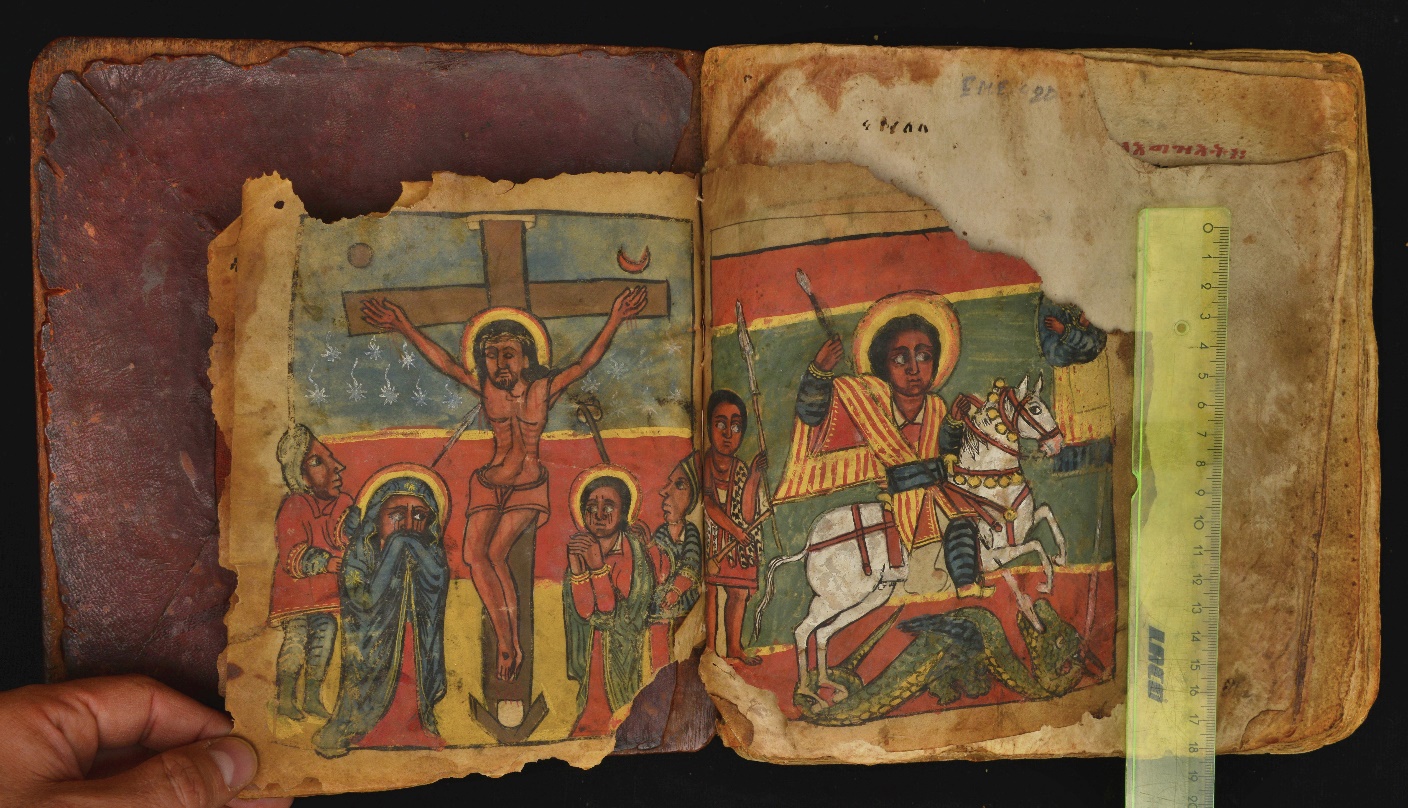

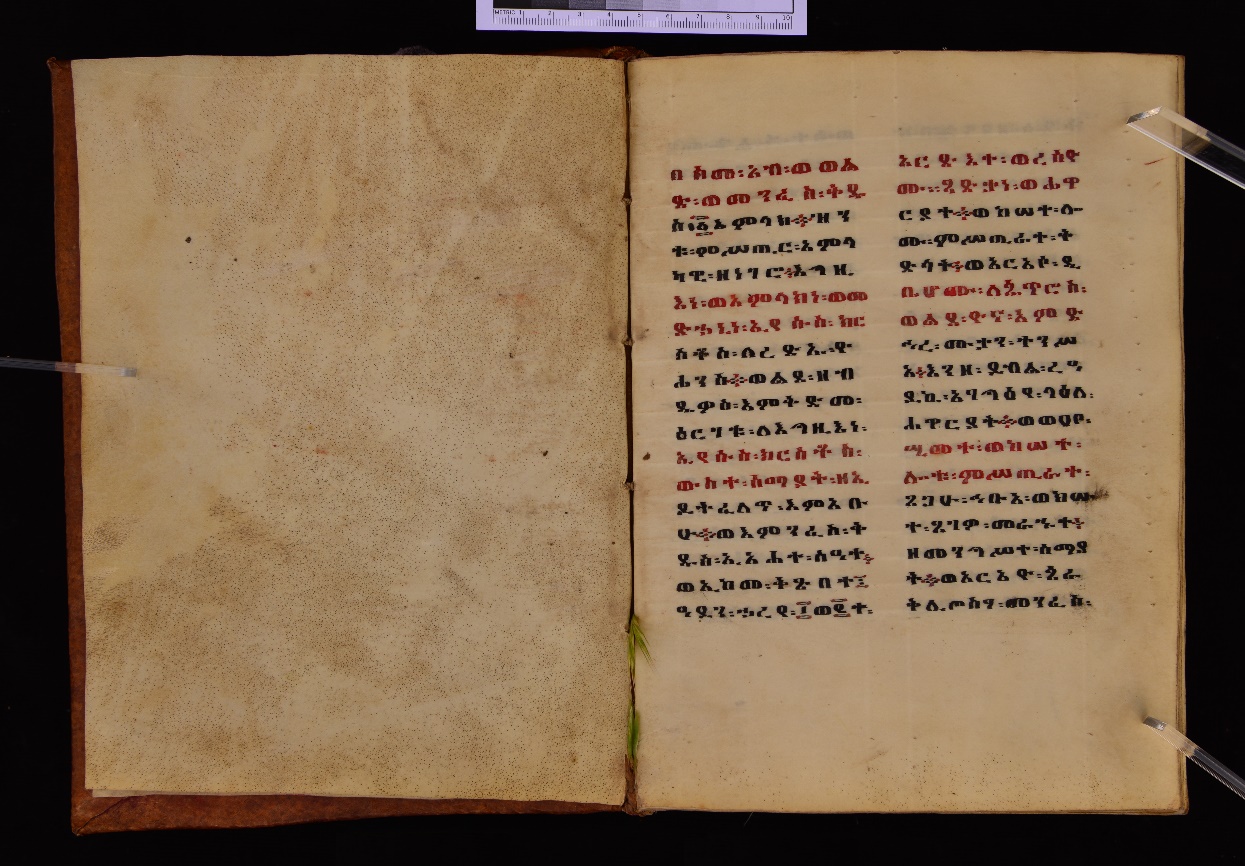

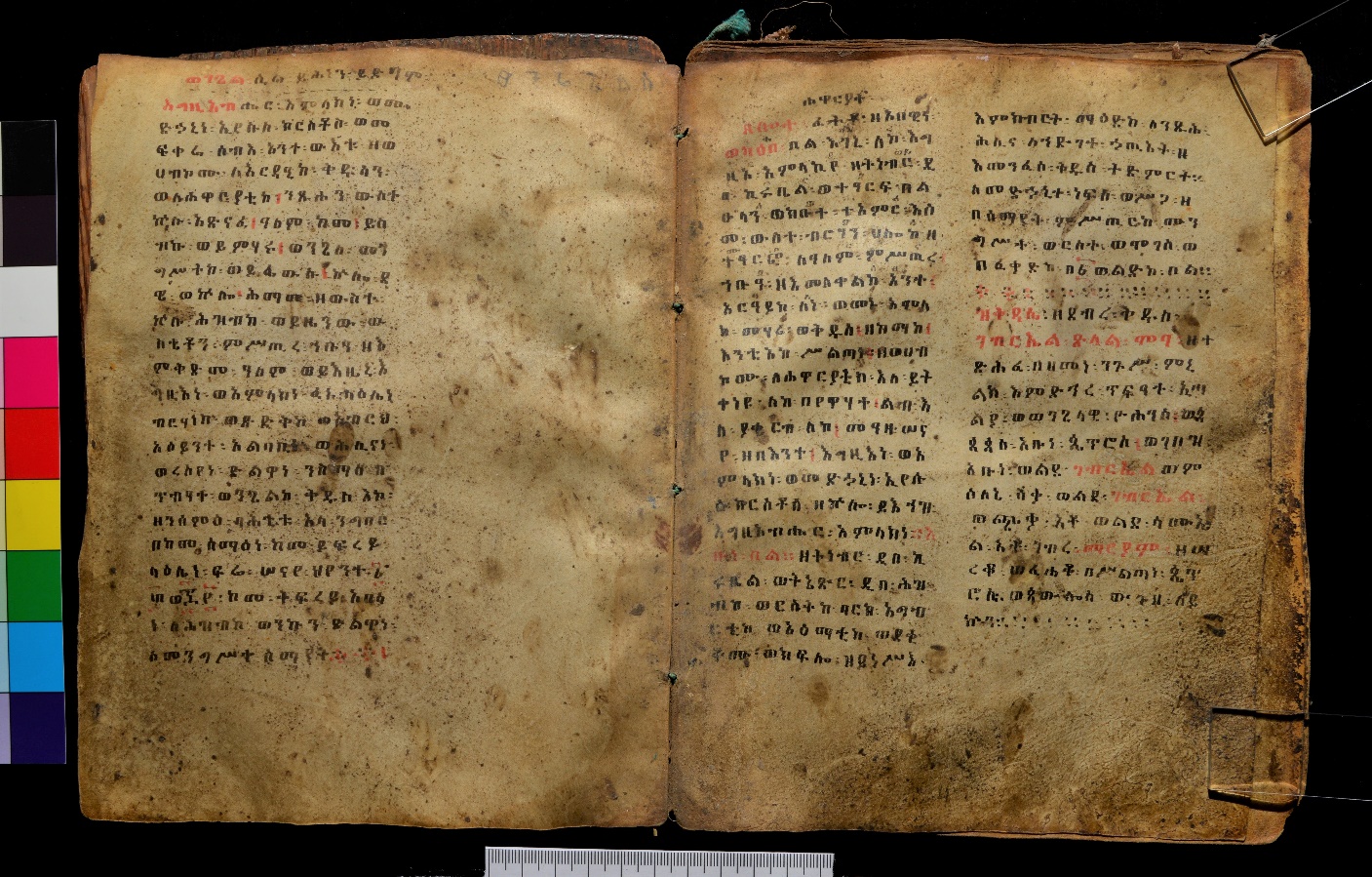

The Four Gospels of the church may be dated to the 18th century, with the preliminary texts (the first two quires) written in a better hand (fig. 9) and the rest in an inferior hand. A finely written Haymanotä ʾAbäw manuscript (fig. 10) and the first half of the Synaxarion with ʾarke-hymns added in the margins (fig. 11), their place in the text columns indicated with small crosses[4], could be possibly datable to the same period. An 18th-/early 19th-century manuscript of the Miracles of Mary contained, apart from later additions, a few fine infixed miniatures (figs 12-13), originating from a different manuscript comparable in age with the main unit (fig. 14).

Fig. 9. ʾƎnda Maryam ʾƎnqwaqo. Four Gospels, 18th century.

Fig. 10. ʾƎnda Maryam ʾƎnqwaqo. Haymanotä ʾabäw, 18th century.

Fig. 11. ʾƎnda Maryam ʾƎnqwaqo. Synaxarion for the 1st half of the year, 18th century.

Fig. 12. ʾƎnda Maryam ʾƎnqwaqo. Miracles of Mary, 18th/early 19th century. Infixed miniatures.

Fig. 13. ʾƎnda Maryam ʾƎnqwaqo. Miracles of Mary, 18th/early 19th century. Infixed miniatures.

Fig. 14. ʾƎnda Maryam ʾƎnqwaqo. Miracles of Mary, 18th/early 19th century. Incipit on the recto-side, additional texts on the verso-side.

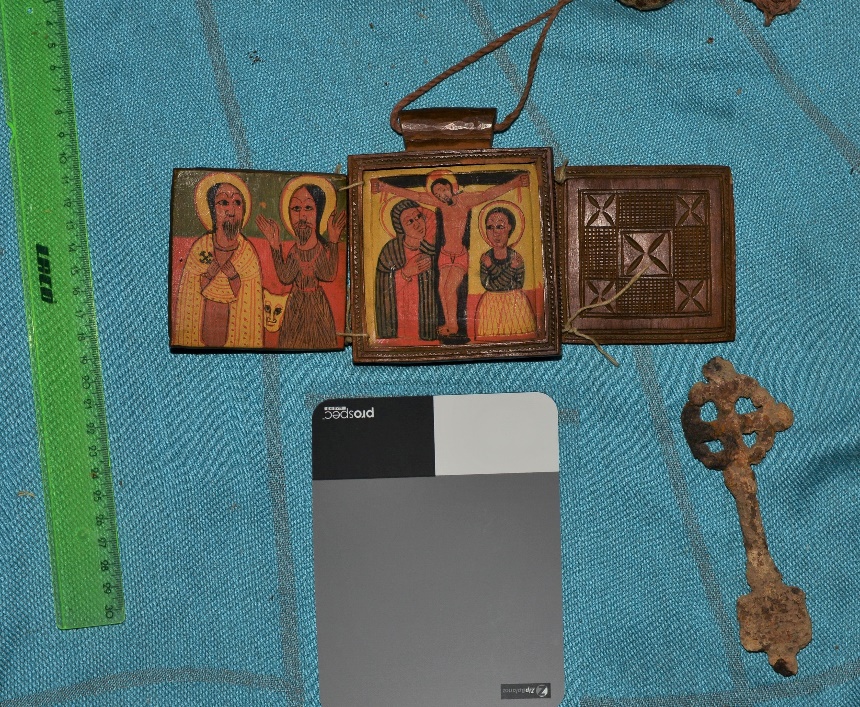

Before the visit, I was told that some ʾAksumite vestiges are preserved at or around the church but nothing could be discovered, at least at a quick look. However, a rosty iron cross was briefly shown to me, of the age difficult to define, said to have been found in the earth, and a small Gondärine triptych (fig. 15), the church reportedly possessing a few more of this kind. Another remarkable object shown was a round stone, of some 30 centimeters in diameter, very heavy, which was said to possess curative power healing sterile women.

Fig. 15. ʾƎnda Maryam ʾƎnqwaqo. Gondärine tryptich and cross.

Zǝqallay Mädḫane ʿAläm Bäräkti, Zǝqallay ʾOm Ṣällim Sǝllaśe

Two small churches, Zǝqallay Bäräkti Mädḫane ʿAläm and Zǝqallay ʾOm Ṣällim Sǝllaśe, could be visited in wäräda Sǝbuḥa Saʿsiʿ (East Tǝgray), tabiya Bäläso[5]. The entire area around is marked by a concentration of ecclesiastical sites. The area of Zǝqallay, extremely rugged, is located southwest from the town ʿƎdaga Ḥamus and represents the southern extremity of the Siʿet flat top mountains chain. On its western slope (in wäräda Ganta ʾAfäšum), the famous rock-church of Gwaḥgot ʾIyäsus stands with a few affiliated churches around[6]. The church Siʿet Maryam is located at its northern end[7]. To reach the area, one drives from ʿƎdaga Ḥamus on a rural road along the slope, passing near another famous rock church, Maryam Dǝngǝlat[8]. Further to the west from Zǝqallay, there are such important rock-hewn churchs as Qiʿat Däbrä Ṣǝyon Maryam and Baḥəra Maryam[9], the built church ʿAzäba Maryam (/Qirqos), the monastery Ḥaräykəwwa ʾƎnda Gäbrä Nazrawi, and others. Advancing further westward, one passes the area of the monastery Däbrä ʿAbbay and reaches the district of ʾAmba Sännayt, the church Wǝqro Maryam[10], the historical district Näbälät and a number of other historical areas, sites and localities which are less known[11], and arrives in the region around ʿAdwa and approaches the vicinities of the monastery ʾƎnda ʾAbba Gärima[12].

Zǝqallay abounds in legends about the 15th-century ʾabunä ʾƎsṭifanos, the famous leader of the Stephanite monastic movement, since the locality is believed to have been the place where ʾƎsṭifanos grew up. Indeed, the Vita of ʾƎsṭifanos accounts that, still before ʾƎsṭifanos’ birth, his father died, and ʾƎsṭifanos was brought up at a place called Zǝqällay, in the family of his uncle[13]. This place may well be the same as today’s Zǝqallay in Sǝbuḥa Saʿsiʿ. Besides, the local tradition says that at one moment ʾƎsṭifanos took the tabot from the monastery of Gundä Gunde and brought it to Zǝqallay, hiding it from King Zärʾa Yaʿqob, the persecutor of the Stephanites. The tabot is told to have stayed there one year, to be later brought to other areas before returning to Gunda Gunde[14].

The round churches Zǝqallay, Bäräkti Mädḫane ʿAläm (fig. 16) and ʾOm Ṣällim Sǝllaśe (fig. 17) look, at least at the first glance, as recent foundations which do not predate the 19th century. Both are small round churches, the mäqdäs of ʾOm Ṣällim Sǝllaśe is partly painted (figs 18-22).

Fig. 16. Zǝqallay Bäräkti Mädḫane ʿAläm. General view.

Fig. 17. Zǝqallay ʾOm Ṣällim Sǝllaśe. General view.

Fig. 18. Zǝqallay ʾOm Ṣällim Sǝllaśe. Painted mäqdäs.

Fig. 19. Zǝqallay ʾOm Ṣällim Sǝllaśe. Painted mäqdäs.

Fig. 20. Zǝqallay ʾOm Ṣällim Sǝllaśe. Painted mäqdäs.

Fig. 21. Zǝqallay ʾOm Ṣällim Sǝllaśe. Painted mäqdäs.

Fig. 22. Zǝqallay ʾOm Ṣällim Sǝllaśe. Painted mäqdäs.

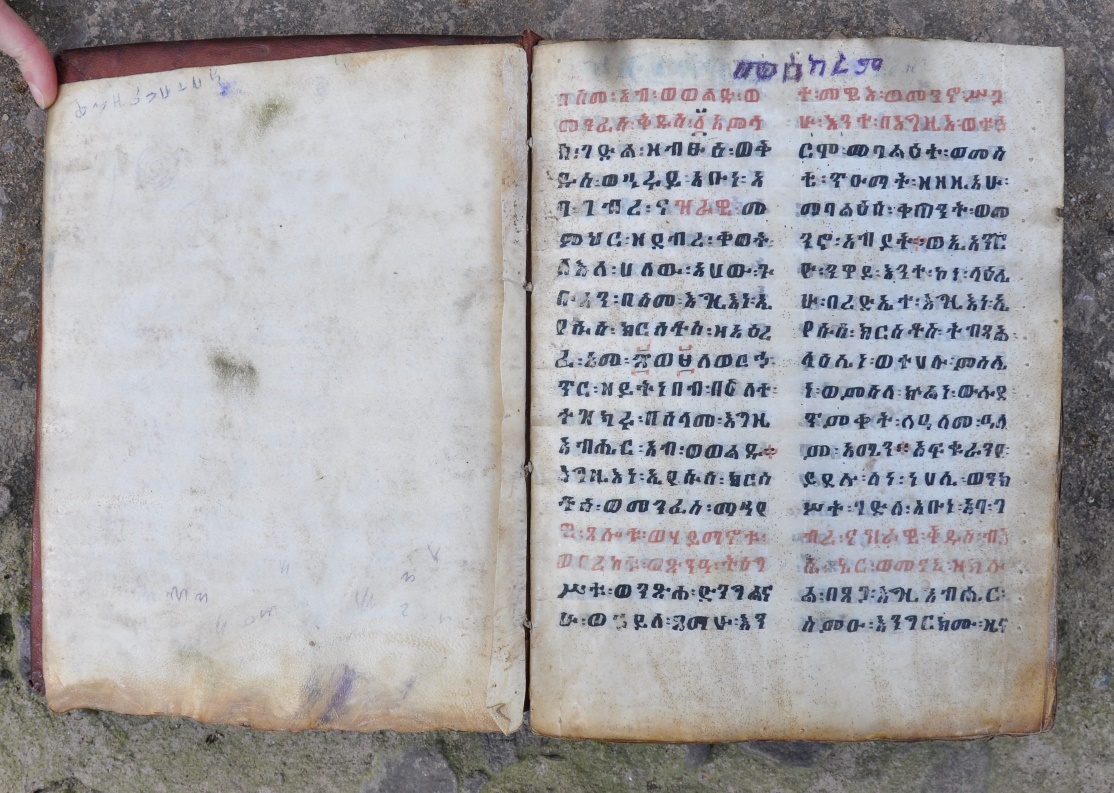

The manuscript collections of these churches are small. As the most interesting items, for Bäräkti Mädḫane ʿAläm one Dǝrsana Mikaʾel manuscript from the time of King Yoḥannǝs IV (r. 1876–1882) has been recorded (fig. 23), and a calligraphically written late 19th-/early 20th-century Miracles of Jesus manuscript (fig. 24).

Fig. 23. Zǝqallay ʾOm Ṣällim Sǝllaśe. Dǝrsana Mikaʾel, 1876–1882. Fol. 2r.

Fig. 24. Zǝqallay ʾOm Ṣällim Sǝllaśe. Miracles of Jesus, late 19th/early 20th century. Fols 2v–3.

May Läbay Däbrä Mäwiʾ Qǝddus Minas

At a later date I was able to visit the church Däbrä Mäwiʾ Qǝddus Minas May Läbay, or ʾƎnda Minas May Läbay (ṭabiya ʾAgʿazi, wäräda Ṣaʿda ʾƎmba) which is located on the plain below the flat top mountain where the churches Bäräkti Mädḫane ʿAläm and ʾOm Ṣällim Sǝllaśe stand. Being at the brink of the flat top mountain, not far from those churches, one can see ʾƎnda Minas May Läbay below. Other foundations located not far from ʾƎnda Minas are the church dedicated to ʾabba Hadära (the same saint as the one venerated in Tämben), the churches ʿAddi Sämaʿt Mädḫane ʿAläm and Däräba ʾArbaʿǝttu ʾƎnsǝsa, and the aforementioned Gwaḥgot ʾIyäsus. May Läbay Qǝddus Minas is said to be formally still a gädam (monastery) but now no monks dwell there. Local priests claimed that one of the “Golden Gospels” books preserved in the city of ʾAksum keeps a record concerning the church. No information about the history of the foundation could be obtained in situ except that the church was established by the local people at an unknown time. The older church building is round and may date to the 19th or early 20th century; a new rectangular larger church was in the process of construction at the time of the visit (figs 25-26). The mäqdäs of the older round church is decorated with murals of recent age (figs 27-31).

Fig. 25. Däbrä Mäwiʾ Qǝddus Minas May Läbay. General view.

Fig. 26. Däbrä Mäwiʾ Qǝddus Minas May Läbay. General view.

Fig. 27. Däbrä Mäwiʾ Qǝddus Minas May Läbay. Painted mäqdäs.

Fig. 28. Däbrä Mäwiʾ Qǝddus Minas May Läbay. Painted mäqdäs.

Fig. 29. Däbrä Mäwiʾ Qǝddus Minas May Läbay. Painted mäqdäs.

Fig. 30. Däbrä Mäwiʾ Qǝddus Minas May Läbay. Painted mäqdäs.

Fig. 31. Däbrä Mäwiʾ Qǝddus Minas May Läbay. Painted mäqdäs.

At a distance of several kilometres, on the top of a huge peak there is a cave church, looking very modest, without any decoration, now deserted and extremely difficult to access (figs 32-33). The local people said that it is dedicated to “Jacob”, with no further details. Some two kilometres away from ʾƎnda Minas there is another small rock-hewn structure, cut in the steep slope of a massive rock, difficult to see from the outside (figs 34-36). The slope around bears traces of work possibly indicative of the constructors’ bigger plans which were not fulfilled (figs 37-38). The structure, of an undefined age[15], was meant as burial chapel, and used in this way until recently, according to the community (figs 39-46). A cavity in the rock half-covered with slabs could be a grave. Now it is empty (figs 45-46). The structure is deserted and not in use for a number of years. The local people could not say anything more specific about it or its relation to ʾƎnda Minas and its community. The presence of other rock-hewn churches around ʾƎnda Minas was mentioned to us several times. All this again proves the suitability of the area for the rock-hewn architecture.

The church of May Läbay Minas owns some 20 to 25 rather recent manuscripts, one small icon and two crosses. One of them was a recent processional bronze cross, of the 19th century, but clearly following in its shape an old 14th-/15th-century model (fig. 47). The second one was a small iron hand-cross which can be dated to the 14th century[16], being a possible hint to the foundation time of the church. Some fragments of parchment manuscripts were found scattered inside the church, probably representig an earlier layer of the local manuscript collection that has nearly completely vanished. Among the manuscripts there was a fine copy of the Acts of St. Minas, completed in the time of Ḫaylä Sǝllaśe I by the scribe Gäbrä Ḥǝywät of the monastery Gunda Gunde, as it was stated in the colophon. The church possesses also a fine recent votive image of St. Minas (fig. 48). The community of May Läbay was exceptionally friendly and hospitable.

Fig. 32. Däbrä Mäwiʾ Qǝddus Minas May Läbay. Cave church on the peak.

Fig. 33. Däbrä Mäwiʾ Qǝddus Minas May Läbay. Cave church on the peak.

Fig. 34. Däbrä Mäwiʾ Qǝddus Minas May Läbay. Burial chapel, entrance from the outside.

Fig. 35. Däbrä Mäwiʾ Qǝddus Minas May Läbay. Burial chapel, entrance from the outside.

Fig. 36. Däbrä Mäwiʾ Qǝddus Minas May Läbay. Burial chapel, entrance from the outside.

Fig. 37. Däbrä Mäwiʾ Qǝddus Minas May Läbay. Traces of hewing on the slope near the burial chapel.

Fig. 38. Däbrä Mäwiʾ Qǝddus Minas May Läbay. Traces of hewing on the slope near the burial chapel.

Fig. 39. Däbrä Mäwiʾ Qǝddus Minas May Läbay. Burial chapel inside.

Fig. 40. Däbrä Mäwiʾ Qǝddus Minas May Läbay. Burial chapel inside.

Fig. 41. Däbrä Mäwiʾ Qǝddus Minas May Läbay. Burial chapel inside.

Fig. 42. Däbrä Mäwiʾ Qǝddus Minas May Läbay. Burial chapel inside.

Fig. 43. Däbrä Mäwiʾ Qǝddus Minas May Läbay. Burial chapel inside.

Fig. 44. Däbrä Mäwiʾ Qǝddus Minas May Läbay. Burial chapel inside.

Fig. 45. Däbrä Mäwiʾ Qǝddus Minas May Läbay. Burial chapel inside, empty grave.

Fig. 46. Däbrä Mäwiʾ Qǝddus Minas May Läbay. Burial chapel inside, empty grave.

Fig. 47. Däbrä Mäwiʾ Qǝddus Minas May Läbay. Processional cross, 18th century.

Fig. 48. Däbrä Mäwiʾ Qǝddus Minas May Läbay. Votive image of St. Minas, 20th/21st century.

Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Däbrä Ṣäḥay Qǝddus Gäbrǝʾel

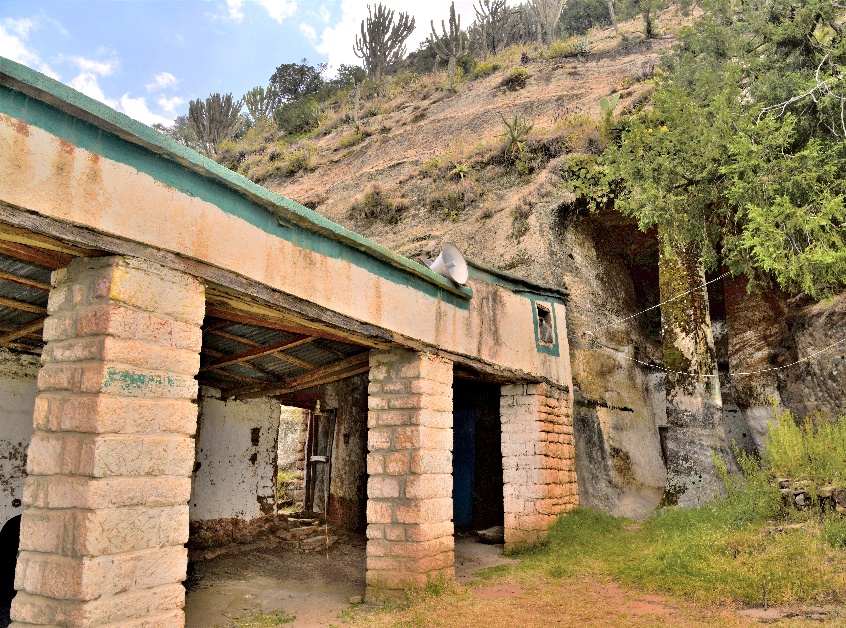

The rock-hewn church of Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Gäbrǝʾel is located in ṭabiya May Mägälta (wäräda Ṣaʿda ʾƎmba), not far from the town ʿƎdaga Ḥamus, a few kilometres away eastwards from the main road to ʿAddigrat. The structure is hidden under a cliff; the spacy church compound is delimited by a wall with a solid gate tower (figs 49-50). Somewhere in the vicinity there is a ṣäbäl-source, and many faithful dwell outside the churchyard under a shelter (fig. 51), hoping for healing. The remarkable church has been rarely mentioned in the scholarly literature[17], and should be certainly better attended by the students of the Ethiopian rock-hewn architecture (cp. some images, figs 52-64). The local tradition claims that the church was founded by King ʿAmdä Ṣǝyon I (r. 1314–1344)[18]. Muslims are said to have lived in the area in the past, but went away at an unspecified time. Also monks reportedly resided around the church, but departed during the “Time of the Princes”[19]. Now Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Gäbrǝʾel is of the most common däbr-status.

Fig. 49. Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Däbrä Ṣäḥay Qǝddus Gäbrǝʾel. Church compound.

Fig. 50. Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Däbrä Ṣäḥay Qǝddus Gäbrǝʾel. Gate tower

Fig. 51. Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Däbrä Ṣäḥay Qǝddus Gäbrǝʾel. Shelter near the church compound.

Fig. 52. Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Däbrä Ṣäḥay Qǝddus Gäbrǝʾel. Entrance to the rock-hewn church.

Fig. 53. Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Däbrä Ṣäḥay Qǝddus Gäbrǝʾel. The church inside.

Fig. 54. Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Däbrä Ṣäḥay Qǝddus Gäbrǝʾel. The church inside.

Fig. 55. Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Däbrä Ṣäḥay Qǝddus Gäbrǝʾel. The church inside.

Fig. 56. Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Däbrä Ṣäḥay Qǝddus Gäbrǝʾel. The church inside.

Fig. 57. Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Däbrä Ṣäḥay Qǝddus Gäbrǝʾel. The church inside.

Fig. 58. Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Däbrä Ṣäḥay Qǝddus Gäbrǝʾel. The church inside.

Fig. 59. Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Däbrä Ṣäḥay Qǝddus Gäbrǝʾel. The church inside.

Fig. 60. Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Däbrä Ṣäḥay Qǝddus Gäbrǝʾel. The church inside.

Fig. 61. Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Däbrä Ṣäḥay Qǝddus Gäbrǝʾel. The church inside.

Fig. 62. Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Däbrä Ṣäḥay Qǝddus Gäbrǝʾel. The church inside.

Fig. 63. Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Däbrä Ṣäḥay Qǝddus Gäbrǝʾel. The church inside.

Fig. 64. Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Däbrä Ṣäḥay Qǝddus Gäbrǝʾel. The church inside.

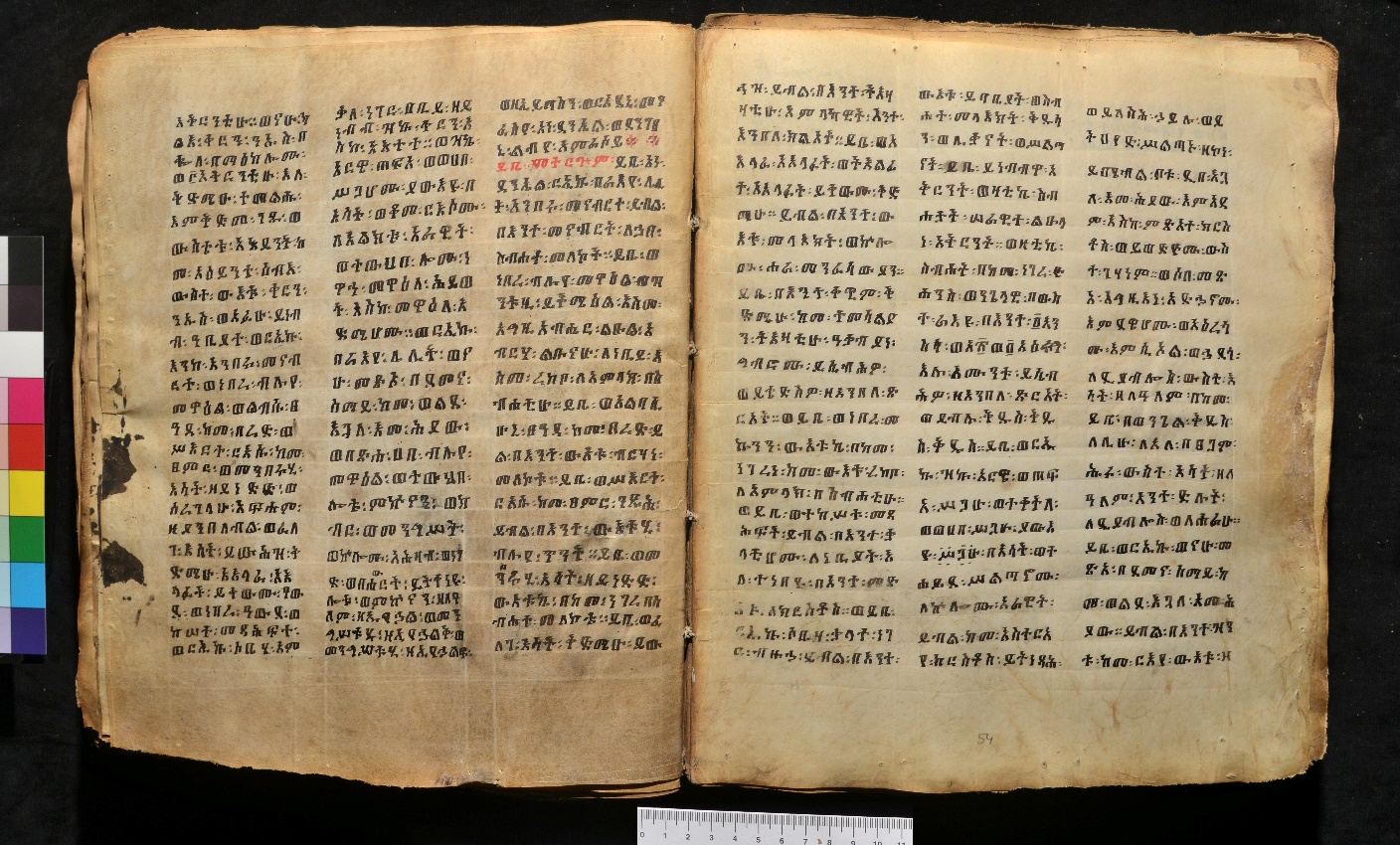

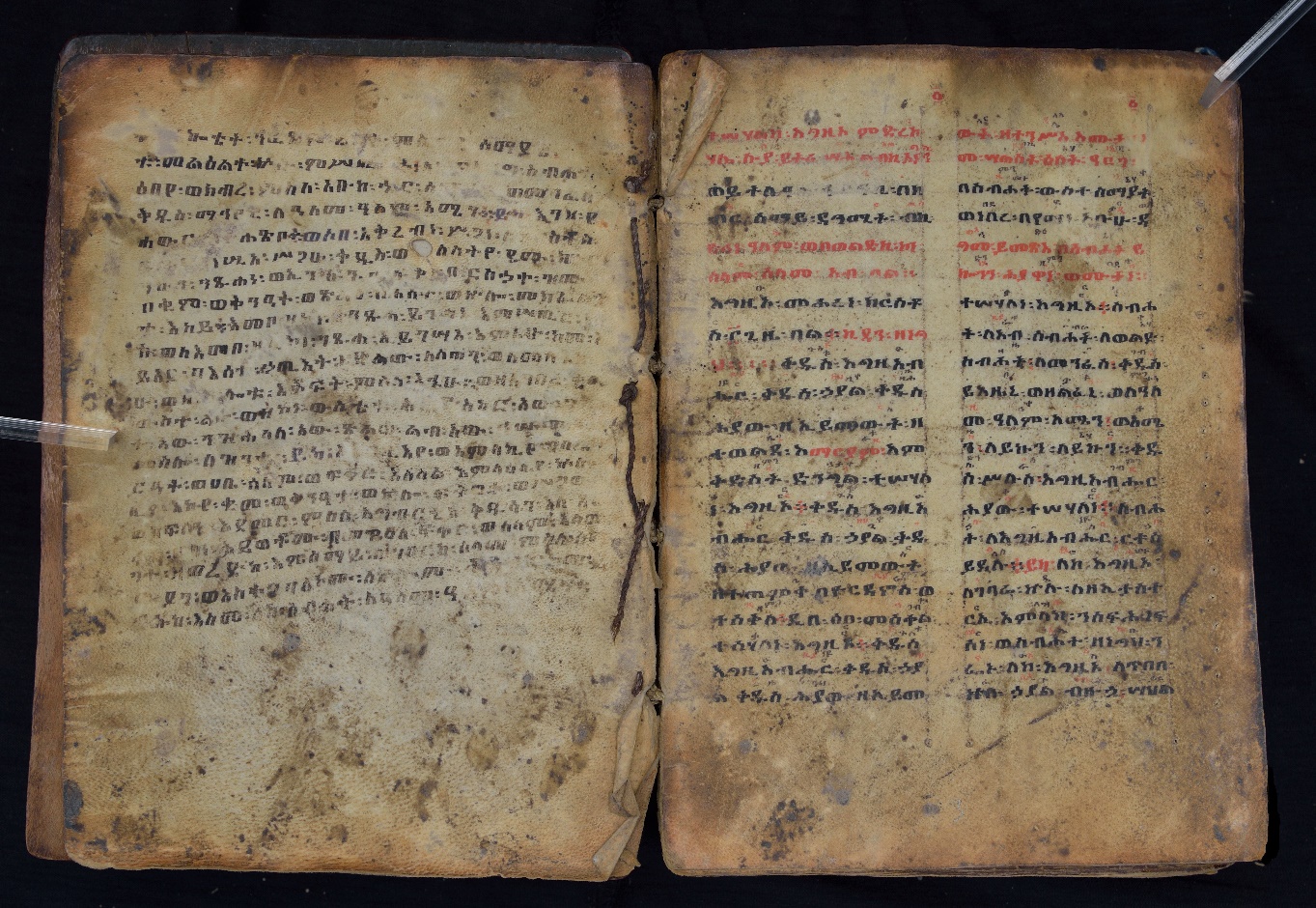

The manuscript collection, though not of a large size, encompasses some interesting manuscripts. A large Gəbra ḥəmamat (“The Book of the Rite of the Passion Week”) manuscript of the church is composed of two production units, incomplete, with some quires misplaced, possibly due to a recent rebinding (see fig. 65). The manuscript is marked by many irregularities concerning the number of written lines, size and shape of the parchment leaves and the written space (fig. 66), and cases of the break of Gregory’s rule (see fig. 67). The reasons for that diversity and the age of the manuscript (19th century?) are difficult to define without a more detailed study.

Fig. 65. Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Däbrä Ṣäḥay Qǝddus Gäbrǝʾel. Mäṣḥafä gəbra ḥəmamat, 19th century. Spine, heterogeneous textblock.

Fig. 66. Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Däbrä Ṣäḥay Qǝddus Gäbrǝʾel. Mäṣḥafä gəbra ḥəmamat, 19th century. Fols 25v–26r.

Fig. 67. Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Däbrä Ṣäḥay Qǝddus Gäbrǝʾel. Mäṣḥafä gəbra ḥəmamat, 19th century. Fol. 53v hair side, fol. 54r flesh side.

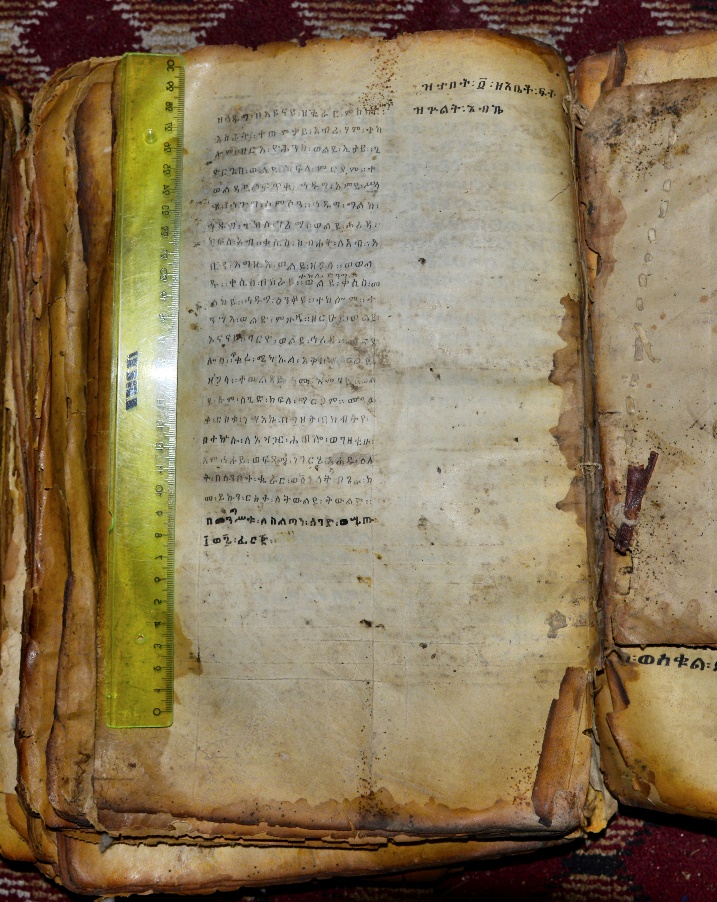

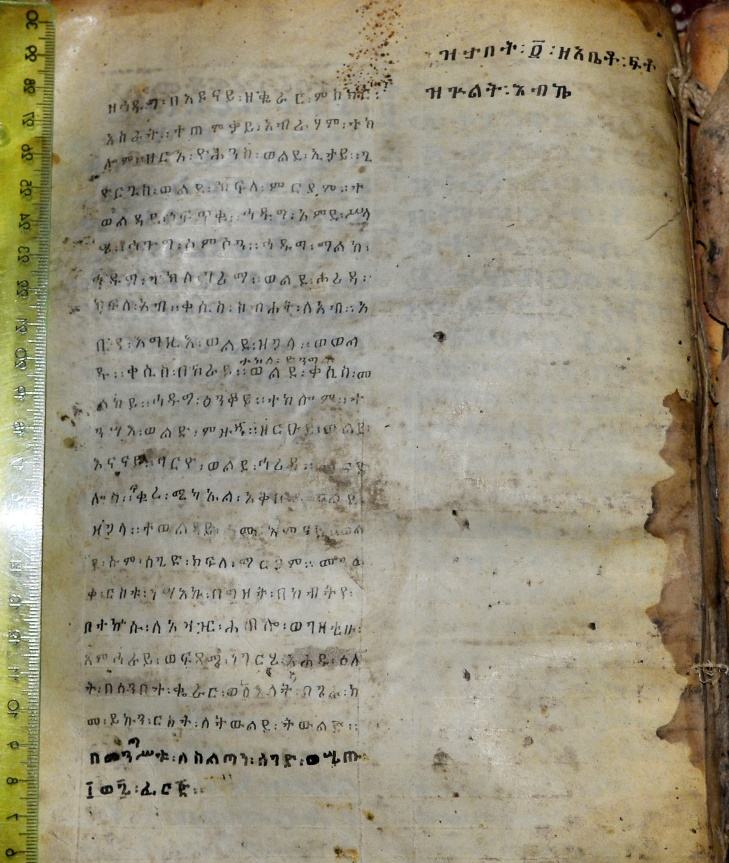

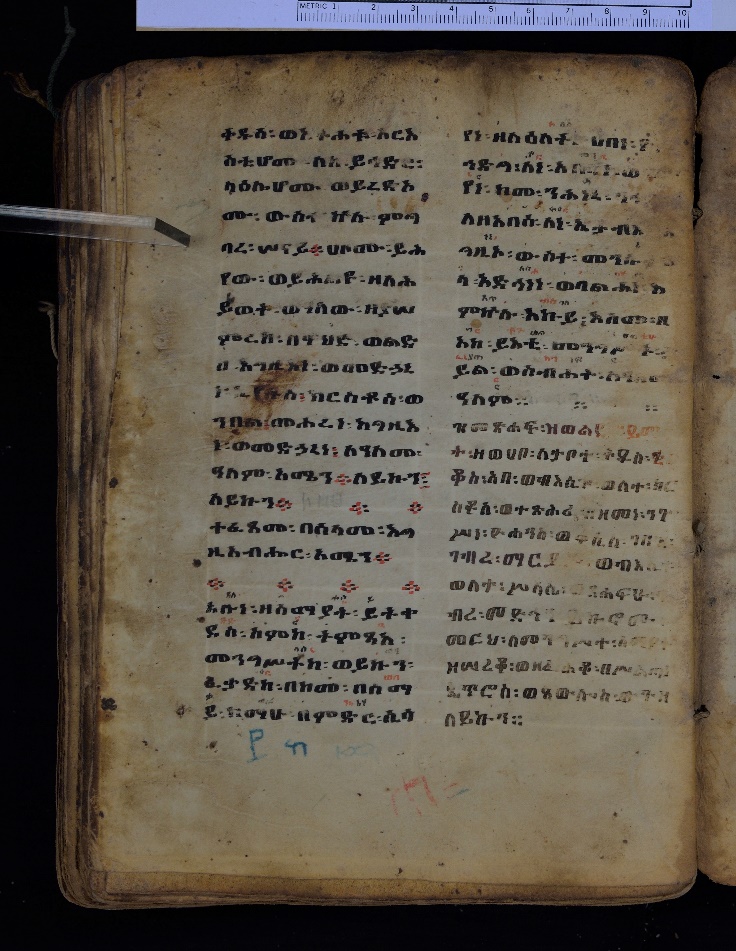

The Four Gospels manuscript of Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Gäbrǝʾel is datable to the second half of the 16th/first half of the 17th century (fig. 68).

Fig. 68. Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Däbrä Ṣäḥay Qǝddus Gäbrǝʾel. Four Gospels, second half of the 16th/first half of the 17th century. Fols 11v–12r, preliminary texts.

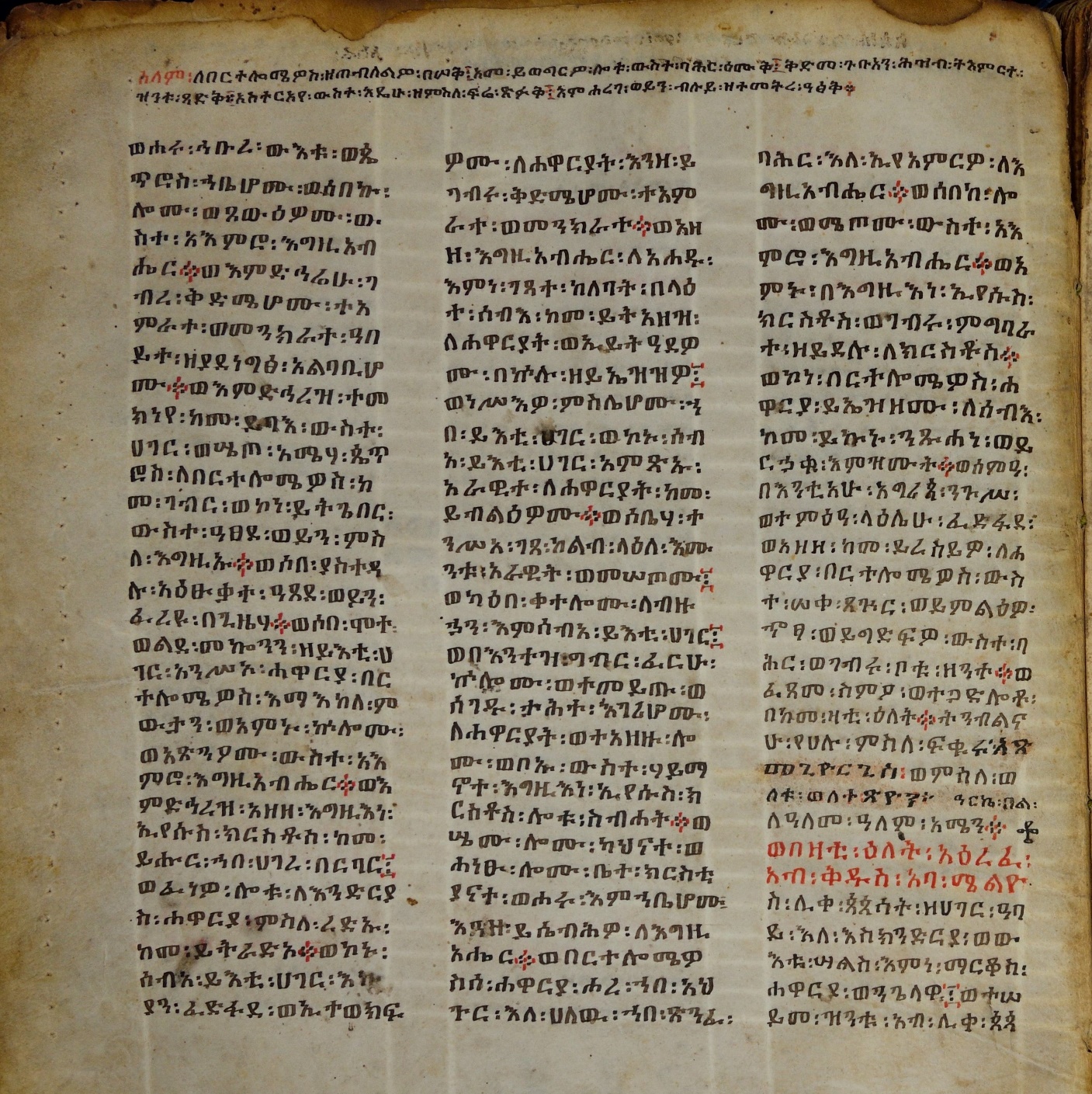

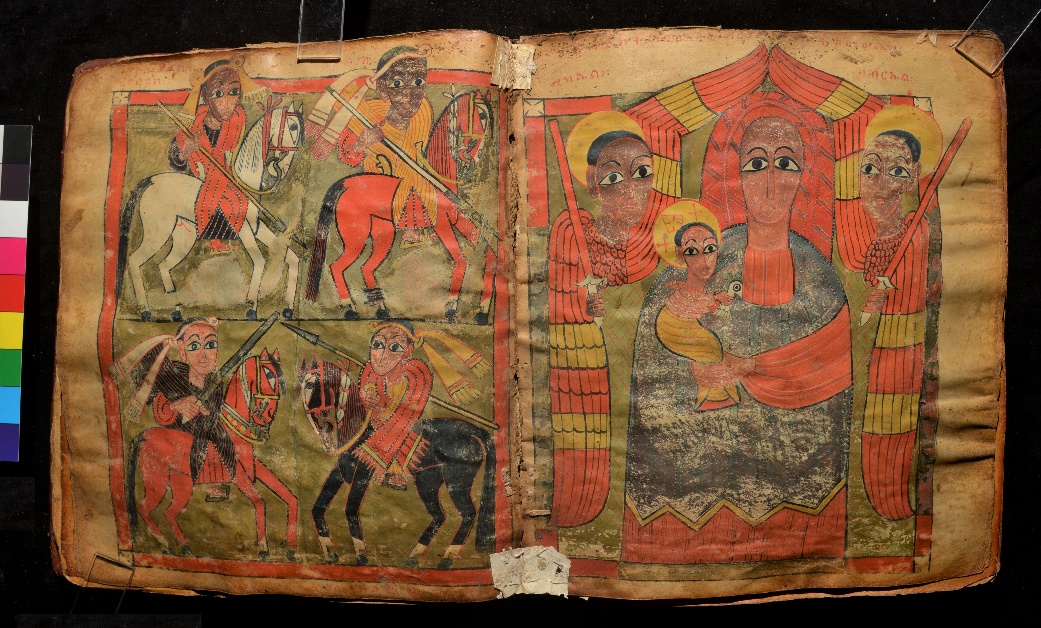

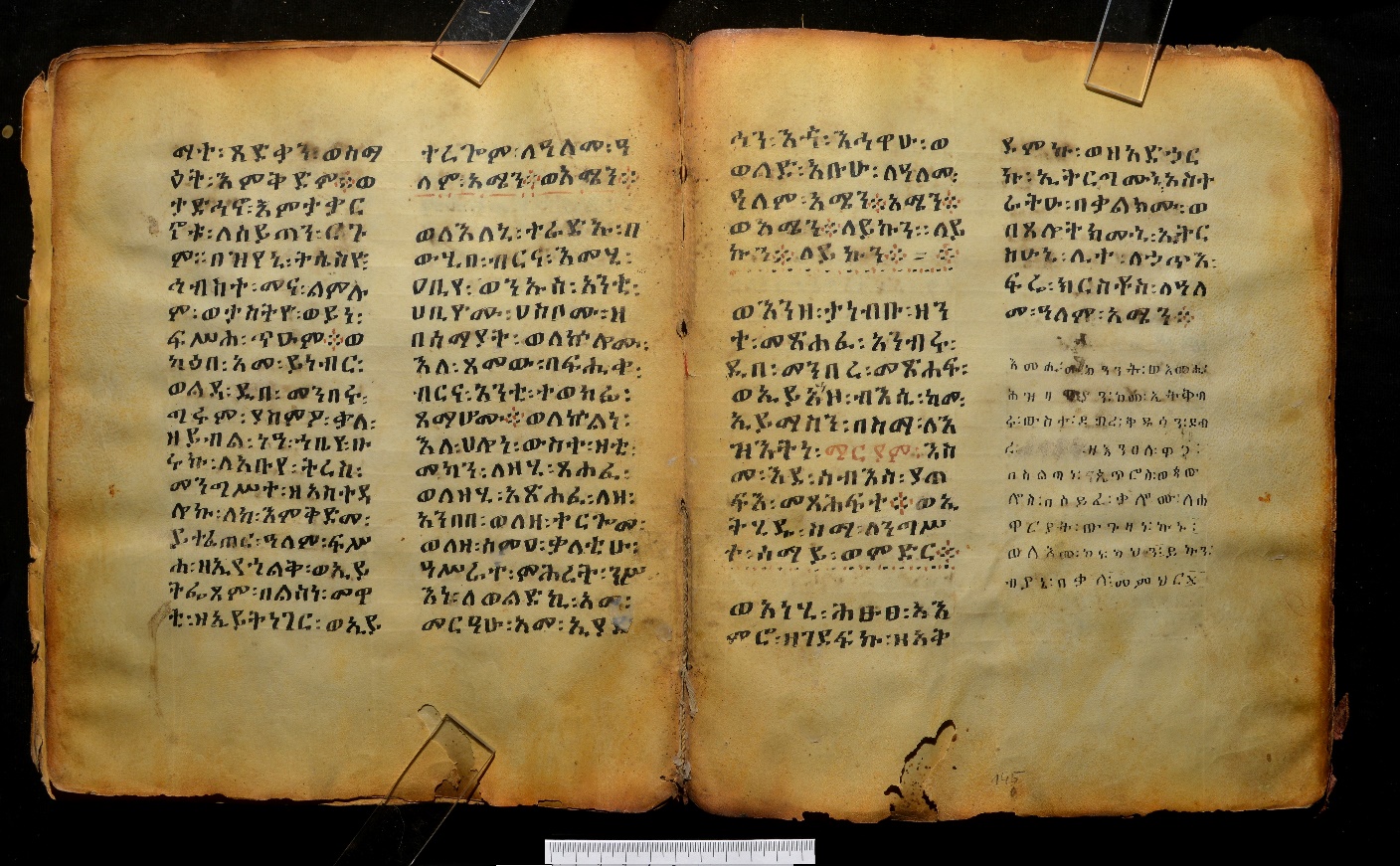

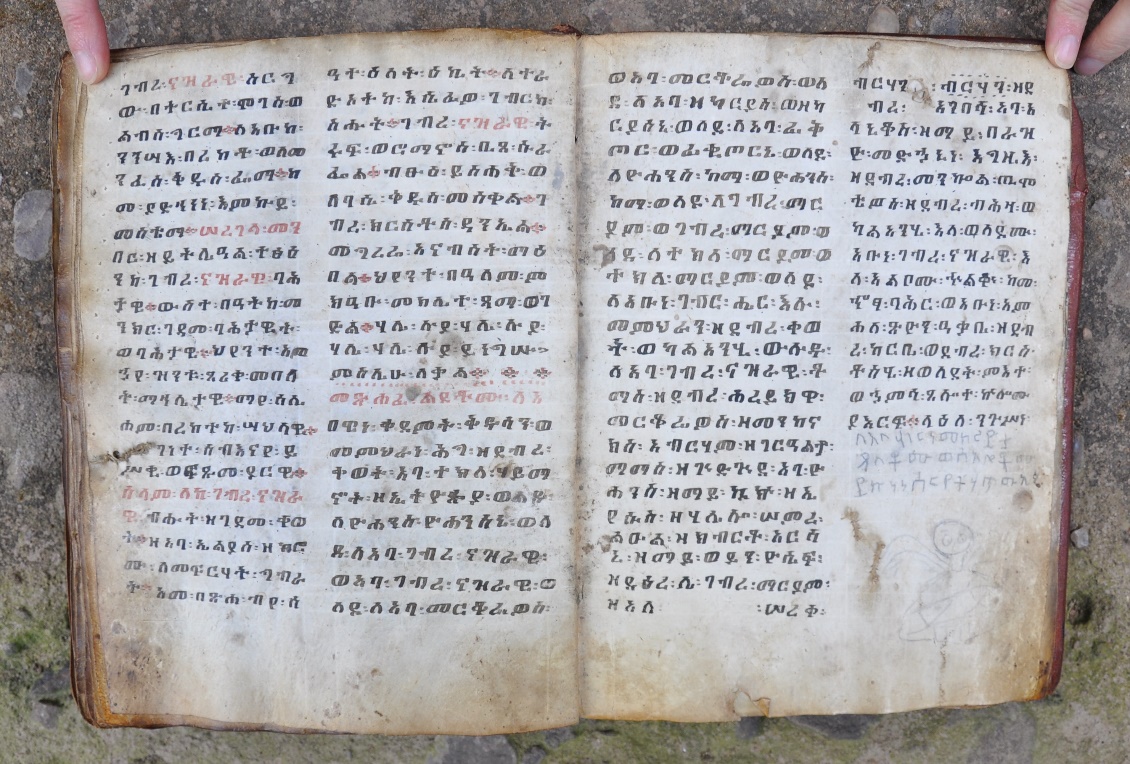

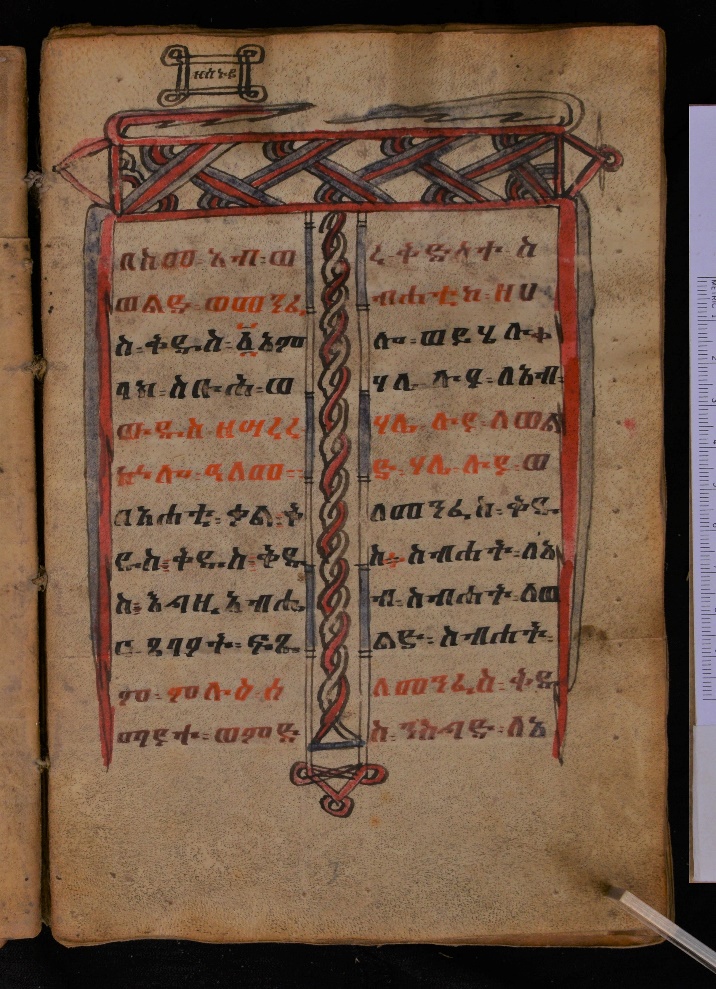

The most remarkable book of the collection is for sure the late 15th-/16th-century Miracles of Mary manuscript. It contains a collection of over 90 stories and a few beautiful miniatures, possibly non-original, added at a later time (figs 69-70). The manuscript shows many repairs and interventions in the binding and the textblock, suggestive of the manuscript’s complex history. The original commissioner might have been ʾabunä Gäbrä Krəstos, possibly the head of a monastic community; the scribe’s name seems to be Fəre Krəstos (fig. 71, fol. 145rb). A monastic genealogy included as additional text hints to a possible connection of the manuscript to the monastic network of Däbrä Libanos of Šäwa (fig. 72). Another additional note mentions King Särṣä Dǝngǝl (r. 1563–1597), and a few more notes are written in another hand of approximately the same period. But a recent (19th-century?) note written in red ink refers to Wäldä ʾAbiyä ʾƎgziʾ and his family members as those who donated the manuscript to the church of (Ṣǝlalmǝʿo) Gäbrǝʾel.

Fig. 69. Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Däbrä Ṣäḥay Qǝddus Gäbrǝʾel. Miracles of Mary, late 15th/first half of the 16th century. Fols 10v–11r, text and miniatures.

Fig. 70. Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Däbrä Ṣäḥay Qǝddus Gäbrǝʾel. Miracles of Mary, late 15th/first half of the 16th century. Fols 11v–12r, miniatures.

Fig. 71. Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Däbrä Ṣäḥay Qǝddus Gäbrǝʾel. Miracles of Mary, late 15th/first half of the 16th century. Fols 144v–145r, explicit, supplication of the scribe, additional note.

Fig. 72. Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Däbrä Ṣäḥay Qǝddus Gäbrǝʾel. Miracles of Mary, late 15th/first half of the 16th century. Fol. 147v, monastic genealogy.

The Missal manuscript of the church was produced in the time of King Mǝnilǝk II (r. 1889–1913), after the “destruction of Italy” (obviously at the battle of ʿAdwa of 1896) as it is stated in the colophon (fig. 73).

Fig. 73. Ṣǝlalmǝʿo Däbrä Ṣäḥay Qǝddus Gäbrǝʾel. Missal, 1889–1913. Fol. 4rb, colophon.

ʾƎnda Ṣadǝqan Mǝḥräta

The church ʾƎnda Ṣadǝqan Mǝḥräta is also located in the ṭabiya May Mägälta (wäräda Ṣaʿda ʾƎmba), close to the town Fərewayni (/Sənqaṭa). The local tradition claims that the church was founded in the time of the “Nine Saints”, but the contemporary rectangular church building is very common and recent. It was hidden in a groove and therefore difficult for photographing (figs 74-76). Another old ruined church was said to have been located somewhere nearby, but it could not be spotted during the time of the visit. ʾƎnda Ṣadǝqan Mǝḥräta has one tabot dedicated to ʾabba Gärima (one of the “Nine Saints”) and another one dedicated to Gäbrä Nazrawi of Qäwät, a saint hardly known so far[20].

Fig. 74. ʾƎnda Ṣadǝqan Mǝḥräta. General view.

Fig. 75. ʾƎnda Ṣadǝqan Mǝḥräta. General view.

Fig. 76. ʾƎnda Ṣadǝqan Mǝḥräta. General view.

No sufficient time was available to look carefully through the manuscript collection of the church on the day of the visit, but it appeared to embrace only recent manuscripts with very common texts. However, at least one manuscript turned out to be remarkable, datable to the second half of the 19th or early 20th century, containing Acts, Miracles and a mälkəʾ-hymn for Gäbrä Nazrawi of Qäwät. These texts were formerly known only indirectly (fig. 77)[21]. The manuscript contains the Vita of Gäbrä Nazrawi’s spiritual father, ʾabba Yoḥannǝs, this text seems to have been unknown so far (fig. 78)[22]. The manuscript includes also a monastic genealogy that starts with Taklä Haymanot “of Ethiopia” who is said to have generated Yoḥannəs whose spiritual son was Gäbrä Nazrawi of Qäwät (fig. 79).

Fig. 77. ʾƎnda Ṣadǝqan Mǝḥräta. Acts, Miracles and Mälkǝʾ of Gäbrä Nazrawi of Qäwät, Acts of Yoḥannǝs, second half of the 19th/20th century. Incipit of the Acts of Gäbrä Nazrawi.

Fig. 78. ʾƎnda Ṣadǝqan Mǝḥräta. Acts, Miracles and Mälkǝʾ of Gäbrä Nazrawi of Qäwät, Acts of Yoḥannǝs, second half of the 19th/20th century. Incipit of the Acts of Yoḥannǝs.

Fig. 79. ʾƎnda Ṣadǝqan Mǝḥräta. Acts, Miracles and Mälkǝʾ of Gäbrä Nazrawi of Qäwät, Acts of Yoḥannǝs, second half of the 19th/20th century. Monastic genealogy.

ʿAba Qəddus Qirqos

The church (ʿAddi) ʿAba[23] Qirqos (/Ḉärqos) is yet another one in the ṭabiya May Mägälta (wäräda Ṣaʿda ʾƎmba), not far from the town Fərewayni. The church, of common rectangular shape, standing on a rock hill, is very modest (figs 80-82).

Fig. 80. ʿAba Qəddus Qirqos. General view.

Fig. 81. ʿAba Qəddus Qirqos. Detail of the church building.

Fig. 82. ʿAba Qəddus Qirqos. Detail of the church building.

Unexpectedly, the manuscript collection turned out to be very interesting, containing a few remarkable manuscripts and objects. The church possesses a Four Gospels manuscript datable to the 17th century (figs 83-84). Two manuscripts containing the Acts of Cyriacus (Qirqos) turned up, both dating to the 19th or early 20th century, a first half of the 19th-century Missal manuscript donated to the church in the time of Yoḥannǝs IV (figs 85-86), and a small 19th-century manuscript with the Prayer of Incense decorated with a fine headpiece (fig. 87).

Fig. 83. ʿAba Qəddus Qirqos. Four Gosples, 17th century. Fols 14v–15r, donation note, incipit of the Gospel of Matthew.

Fig. 84. ʿAba Qəddus Qirqos. Four Gosples, 17th century. Fol. 61r, Gospel of Mark.

Fig. 85. ʿAba Qəddus Qirqos. Missal, first half of the 19th century. Fols 1v–2r.

Fig. 86. ʿAba Qəddus Qirqos. Missal, first half of the 19th century. Fol. 144v. Donation note.

Fig. 87. ʿAba Qəddus Qirqos. Prayer of Incense, 19th century. Fol. 3r. Incipit, headpiece.

Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam

At the distance of a few kilometres from the southern outskirt of the town ʿƎdaga Ḥamus (wäräda Sǝbuḥa Saʿsiʿ) there is the church Today Ṭaqot ʾƎnda Ṣəyon (/Däbrä Ṣəyon) Maryam, yet another one of the numerous ecclesiastic sites located along the road which connects Mekelle to ʿAddigrat and leads further into Eritrea towards the Red Sea. Today Ṭaqot Maryam is a large rectangular church with a spacious church compound and a massive gate tower (figs. 88-90)[24]. The tabots of Ṭaqot Maryam are said to be three, dedicated to St Mary, ʾUraʾel and the holy kings ʾAbrəha and ʾAṣbəḥa. Ṭaqot Maryam reportedly possesses a considerable manuscript collection but it was not accessible on the day of the visit.

Fig. 88. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. General view.

Fig. 89. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. General view.

Fig. 90. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. Gate tower.

At a distance of some two hundred meters from the church there is a remarkable structure hewn from a stone rock overlooking the valley below. It is called the (deserted) rock-hewn church of Ṭaqot[25]; the local people call it näkwal ʿəmni (Tgn. “stone with holes”) due to its peculiar shape (figs 91-114). The structure bears no obviously Christian symbols and shows a minimum of decorations.

Fig. 91. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. Rock-hewn church, general view.

Fig. 92. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. Rock-hewn church, general view.

Fig. 93. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. Rock-hewn church, general view.

Fig. 94. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. Rock-hewn church, general view.

Fig. 95. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. Rock-hewn church, details.

Fig. 96. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. Rock-hewn church, details.

Fig. 97. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. View around the rock-hewn church.

Fig. 98. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. View around the rock-hewn church.

Fig. 99. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. Archaeological area outside the church compound.

Fig. 100. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. Rock-hewn church, details.

Fig. 101. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. Rock-hewn church, details.

Fig. 102. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. Rock-hewn church, details.

Fig. 103. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. Rock-hewn church, details.

Fig. 104. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. Rock-hewn church, details.

Fig. 105. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. Rock-hewn church, details.

Fig. 106. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. Rock-hewn church, details.

Fig. 107. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. Rock-hewn church, details.

Fig. 108. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. Rock-hewn church, details.

Fig. 109. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. Rock-hewn church, details.

Fig. 110. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. Rock-hewn church, details.

Fig. 111. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. Rock-hewn church, details.

Fig. 112. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. Rock-hewn church, details.

Fig. 113. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. Rock-hewn church, details.

Fig. 114. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. Rock-hewn church, details.

On the way to the näkwal ʿəmni, just outside the compound of the modern church Ṭaqot Maryam, there is a spot where the construction of a new bigger church started a few years ago (fig. 99) but the work was interrupted as soon as archaeological remains of an old settlement were unearthed. Comparing the western facade of the church as it appears in the photo printed in Ricci 1961[26] with its contemporary shape (fig. 89), one may assume that the church was heavily rebuilt but escaped the full demolition and was not substituted for with a completely new structure. The contemporary church building stands on an ancient stone foundation that is laid bare and well visible (figs 115-123). Inside the church compound, some ʾAksumite vestiges are visible (figs 89, 115-116, 124), and much more probably remains under the earth.

Fig. 115. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. ʾAksumite vestiges, foundation under the recent church.

Fig. 116. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. ʾAksumite vestiges, foundation under the recent church.

Fig. 117. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. ʾAksumite foundation under the recent church.

Fig. 118. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. ʾAksumite foundation under the recent church.

Fig. 119. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. ʾAksumite foundation under the recent church.

Fig. 120. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. ʾAksumite foundation under the recent church.

Fig. 121. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. ʾAksumite foundation under the recent church.

Fig. 122. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. ʾAksumite foundation under the recent church.

Fig. 123. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. ʾAksumite foundation under the recent church.

Fig. 124. Ṭaqot Maryam ʾƎnda Ṣəyon Maryam. ʾAksumite vestiges near the recent church.

Quoted bibliography

- Ambu, M. 2022, Du texte à la communauté : relations et échanges entre l'Egypte copte et les réseaux monastiques éthiopiens (XIIIe-XVIe siècle), Thèse de doctorat en Histoire, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne.

- Ancel, S. 2013, “Historical Overview of the Church of Addiqäharsi Päraqlitos”, In Ecclesiastic Landscape of North Ethiopia: Proceedings of the International Workshop, Ecclesiastic Landscape of North Ethiopia: History, Change and Cultural Heritage. Hamburg, July 15-16, 2011, ed. D. Nosnitsin. Supplement to Aethiopica 2. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 91–105.

- Gerster, G. 1972. Kirchen im Fels: Entdeckungen in Äthiopien. Zürich, Freibung im Breisgau: Atlantis (2. Auflage).

- Getatchew Haile, William F. Macomber 1982. A Catalogue of Ethiopian Manuscripts Microfilmed for the Ethiopian Manuscript Microfilm Library, Addis Ababa, and for the Hill Monastic Manuscript Library, Collegeville, VI: Project Numbers 2001–2500. Collegeville, MN: Hill Monastic Manuscript Library, St. John’s Abbey and University.

- Getatchew Haile 2006 (ed.). The Gǝʿǝz Acts of Abba Ǝsṭifanos of Gwǝndagwǝnde (Text). Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium 619, Scriptores Aethiopici, 110. Lovanii: In aedibus Peeters.

- Getatchew Haile 2006 (tr.). The Gǝʿǝz Acts of Abba Ǝsṭifanos of Gwǝndagwǝnde. Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium 620, Scriptores Aethiopici, 111. Lovanii: In aedibus Peeters.

- Getatchew Haile 2016. “The Marginal Notes in the Abba Gärima Gospels”. Aethiopica 19, pp. 7–26.

- Godet, É. 1977. “Répertoire des sites pré-axoumites et axoumites du Tigre”, Abbay 8, pp. 19–52.

- Kim, S. 2022. “New Studies of the Structure and the Texts of Abba Garima Ethiopian Gospels”, Afriques13 [https://doi.org/10.4000/afriques.3494].

- Leake Teklebrhan 2019. A History of Däbrä Bekur Abunä Sét Monastery in Hahaile, Ahiferom Wäräda Tigray, Ethiopia, from Its Foundation up to 1991. PhD Thesis Addis Abeba University, Department of History.

- Lusini, G. 2005. “Danǝʾel of Däbrä Maryam”. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, ed. by Siegbert Uhlig, II:85a–86a. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Muehlbauer, M. 2020. “A Rock-Hewn Yǝmrǝḥannä Krǝstos? An Investigation into Possible ‘Northern’ Zagwe Churches near ʿAddigrat, Tǝgray”, Aethiopica 23, pp. 31–56.

- Nosnitsin, D. 2005. “Gäbrä Nazrawi”. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, ed. by Siegbert Uhlig, II:626a–27. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Ricci, L. 1961. “Antichità nello ʿAgāmē”. Rassegna di Studi Etiopici 17, pp. 116–18.

- Sauter, R. 1963. “Où en est notre connaissance des églises rupestres d’Éthiopie’. Annales d’Éthiopie 5, pp. 235–292.

- Sauter, R. 1976. “Églises rupestres au Tigre”. Annales d’Éthiopie 10, pp. 157–175.

[1] For the assistance in organization and carrying out the field research trips, I am grateful to Mr Mearg Abay (Tigray Culture and Tourism Bureau [TCTB]), Mr Hagos Gebremariam (Adigrat University), His Holiness Abuna Makaryos Archbishop of Axum Central Tigray Zone Diocese, to Dr Magdalena Krzyzanowska (Universität Hamburg), and all other people who helped my research in various ways.

[2]According to my knowledge, only two of the nine churches mentioned below appear in the research literature. There is no information on the manuscript collection of the last institution (see below), yet I decided to include it into the report for the purpose of completeness, and to enhance the photographic material on the site which has been meagre.

[3]Contrary to the initial claims of the church possessing around 100 books.

[4] Sometimes a directive is added, ዓርኬ፡በል፡‘say the ʿarke-hymn’.

[5] In 2019, the former large wäräda Saʿsiʿ Ṣaʿda ʾƎmba was split into two administrative units, wäräda Sǝbuḥa Saʿsiʿ (with the administrative centre in the town ʿƎdaga Ḥamus), and wäräda Ṣaʿda ʾƎmba (the capital Fərewayni (/Sənqaṭa)) [I thank Mr. Hagos Gebremariam for this detail].

[6] According to a recent research, Gwaḥgot ʾIyäsus is a “hewn copy” of the free-standing church of Yǝmrǝḥannä Krǝstos in Lasta (see Muehlbauer 2020:32). Using the occassion, I want to add to the information provided in Muehlbauer 2020:36, fn. 31, that twelve manuscripts from the collection of Gwaḥgot ʾIyäsus and two other church objects (a cross and a lectern) have been described in the database of the project Ethio-SPaRe (https://mycms-vs03.rrz.uni-hamburg.de/domlib/receive/domlib_institution_00000117). The local tradition speaks of seven churches under the administration of Gwaḥgot ʾIyäsus, though dedications of ony five could be ascertained during my former visit (St. Mary, George of Lydda, Saviour of the World, ʾArägawi). Another significant chuch, dedicated to the Three Children in the Furnace (Sälästu Däqiq), is located not far Gwaḥgot ʾIyäsus but appears to be independent. Mr. Hagos Gebremariam recently brought to my attention a sizable hagiographical work in Gəʿəz, Gädlu lä-sälästu däqiq ʾAnanya wä-ʾAzarya wä-Misaʾel (“Vita of the Three Children, Hananiah, Azariah and Mishael”) previously unknown, attested in at least one recent manuscript. It mentions some historical events that took place around the church, including the 16th-century Muslim wars. The local community seems to be preparing a printed edition of this work.

[7]The area is sometimes referred to as “Haramat mountains“.

[8] Shortly before the outbreak of the conflict, a project aimed at facilitating the entrance to the church by new means of ascent was completed (March 2019), carried out by a few Italian professionals and local enthusiasts (cp. https://www.mountainwilderness.org/2019/04/06/mountain-wilderness-in-ethiopia-a-resounding-success/ [accessed on 15.08.2023]).

[9] Sixteen sites could be reached by the team of Ethio-SpaRe in 2010–2015 in this wide part of Ganta ʾAfäšum district, which is delimited by the main roads ʿAddigrat – ʿAdwa and ʿAddigrat – Mäqälä (Nosnitsin 2013, chapter 3, see also p. xx and the map on p. xxiii), while many more remained out of the reach. In that period the area lacked roads and travelling was very difficult.

[10] On the identification of this church in the sixteenth-century narrative of Francisco Alvares, see Ancel 2013:94-95.

[11] One of the historical place names to be found there is the monastery Däbrä Ḥamlo. It is mentioned in an additional note/colophon included in the important Ms. EMML no. 2514 “Acts oft he Martyrs”, recently analyzed by Martina Ambu (Ambu 2022:104-107); and probably in one of the additional notes in the ʾƎnda Abba Gärima Gospels I (Ḥamlo in ʾAmba Sǝnäyt, see Getatchew Haile 2016:8, 9, 20). The volume was kept in the church ʾAstit Kidanä Mǝḥrat in ʾAnkobär when microfilmed (Getatchew Haile – Macomber 1982:5-14), but according to the colophon it appears to have been written in the place called Däbrä Ḥamlo (datings of the manuscript range from the late 14th to the early 16th centuries, see Ambu 2022:98), probably a monastery said to have been elevated in the time of King Dawit (r. 1382–1413) and Metropolitan Sälama (in tenure 1348-1388). Däbrä Ḥamlo may be identical to ʾƎmba (Ṣaʿdat) Ḥamlo (14,1759°, 39,3092°), with the landscape strikingly similar including a reference to the height of place (a rock?) where Däbrä Ḥamlo stood, that can be reached only with the helpf of a rope of “132 elbows” (see Ambu 2022:104). This corresponds exactly to the most remarkable physical feature of today’s ʾƎmba Ḥamlo (cp. a photo https://www.facebook.com/381633372388258/posts/413209039230691[accessed 14.08.2023]).

[12] The entire area is located northward from the main A2 road leading from ʿAddigrat to the city of ʾAksum. While preparing the report, I came across a couple of place names which, when identified, can contribute to the understanding of Ethiopic sources. For instance, cp. the article Kim 2022 and the hypothesis concerning the origin of the volume ʾƎnda ʾAbba Gärima Four Gospels II, which is proposed to be seen in the monastery Dabrä Sina/ ʾƎnda ʾAbba Yoḥanni (Eritrea), basing on the interpretation of an additional note (C9, see Kim 2022:30-31, 46). It is quite possible that Däbrä Sina mentioned in the note is a monastery in Eritrea and the recorded donation concerns that institution (following Kim 2022:30-31). However, ʾAḫaḥayle, the area mentioned in the land document, does not appear to be unknown (as said in Kim 2022:43). In my opinion, it corresponds to Ḥaḥayle, located to the northeast from the monastery ʾƎnda Abba Gärima, a historical region and today a wäräda with the central city Färäsmay (formerly a part of the ʾAḥfärom wäräda). [As a sad coincidence, the social media have recently reported about a fire that happened in the church ʾƎnda Ğäwärğǝs (Giyorgis), ṭabiya ʿAddi ʿƎqoro, wäräda Ḥaḥaylä, which destroyed it’s sizable library]. ʾAbba Set under whose administration ʾAḫaḥayle was placed, according to the note C9, reminds of ʾabuna Set of Däbrä Bäkwǝr, a monastery located also in Ḥaḥayle (Leake Teklebrhan 2019, though ʾabunä Set does not match precisely King Yəsḥaq in terms of chronology). The inclusion of this legal document into the ʾƎnda ʾAbba Gärima Gospels is logical because it was meant to document the transfer of the authority over (and the tributes from) the neighbouring region (ʾAḫāḥayle/ Ḥaḥayle) to another distant institution (Däbrä Sina). The Four Gospels manuscript executes its classical “archival” function in this case, being used as repository of legal documents. It cannot be excluded that a document very similar to the note C9 will once turn up in Däbrä Sina. In my opinion, the note is unlikely an indication that the entire manuscript was produced in Däbrä Sina.

[13]ወእንዘ፡ሀሎ፡ውስተ፡ከርሠ፡እሙ፡ሞተ፡አቡሁ።ወሶበ፡ተወልደ፡ሰመይዎ፡ኀድገ፡አንበሳ።ወሐነፀቶ፡እሙ፡ወልህቀ፡በቤተ፡እኅወ፡አቡሁ፡በምድር፡እንተ፡ይብልዋ፡ዝቀላይ። (Getatchew Haile 2006a:1), “While he was still in the womb of his mother, his father died. When he was born, they named him Ḫädgä Anbäsa. His mother reared him; and he grew up in the home of his father’s brother, in a district called Zǝqälay.” (Getatchew Haile 2006b:1). The passage and the place name have the same shape also in the two church editions of the Vita of Estifanos (cp. also http://dehayagame.blogspot.com/2016/01/dehay-agame-adigrat-1262-1500-1406-1500.html [accessed on 16.08.2023]).

[14] Another historical place of prominence located near Zǝqallay is ʾAkora where a battle between ras Sǝbḥat of ʿAgamä and Gäbrä Śǝllase Barya Gabǝr of ʿAdwa took place in 1914 (EAE IV, 588-589) and resulted in the death of Sǝbḥat.

[15]A postcard hanging on a stick inside the church, probably left by some foreign visitors, had the date 1967 CE.

[16]I thank Prof. Ewa Balicka-Witakowska (Uppsala) for help in dating the objects.

[17]Not appearing in Sauter 1963 and only mentioned in Sauter 1976 (no. 1103), with no further details and a small bibliography of three items, including the pioneering book of Georg Gerster (the second edition, see below).

[18] Other data have been reported in Gerster 1972:147, underscoring the variability of the tradition over the span of some 55 years. According to this publication, the local tradition places the foundation in the time of King Yǝkunno ʾAmlak (r. 1270–1285) and assignes it to ʾabba Danǝʾel of Qorqor, the spiritual father of ʾabunä ʾEwosṭatewos (Lusini 2005).

[19]Zämänä mäsafənt, a period of extreme decentralization of the Ethiopian state (1769–1855).

[20]Gäbrä Nazrawi of Qäwät, Qäwat or Qäʿät (supposedly the monastery Däbrä Sina, located in Northern Šäwa Zone, Yǝfat and Ṭǝmmuga, the place called Qäwat (different from the one mentioned above)). There is at least one saint called by the same name, known from the district of Wälqayt. Gäbrä Nazrawi of Qäwät was somehow related to ʾabba ʾAron of Däbrä Daret (Däbrä ʾAbuna ʾAron) in the district of Mäqet, today a wäräda in Amhara Region, Semien Wollo Zone. The saint is briefly commemorated in the Ethiopic Synaxarion on 10 Ṭǝqǝmt and 29 Ṭǝrr (see Nosnitsin 2005).

[21] Cp. Kinefe-Rigb Zelleke 1975, no. 67.

[22] Also it contradicts the information indicated above. Obviously, the uncertainities can be solved only after a detailed study of the relevant hagiographic traditions.

[23] The pronunciation ʾAba appears to be acceptable as well.

[24]On there other side of the road, there is a recent church Ṭaqot Kidanä Mǝḥrät related to the ras Mängäša Yoḥannǝs of Tǝgray (1865–1906).

[25] Cp. Ricci 1961. On the site see also Sauter 1963, no. 11; Sauter 1976, no. 11, Godet 1977:46.

[26]One of the few or maybe even the only one available, see Ricci 1961, fig. 2.