Field Research 2018-2019

Beta maṣāḥǝft working papers 2

After Ethio-SPaRe: Beta maṣāḥǝft Field Research

Part 2: Lǝggat Qirqos and its Bookmaking

Mission report: read online or download PDF file.

DOI: 10.25592/uhhfdm.13988

Public Report

Lǝggat Qirqos, Gulo Mäkäda district, East Tigray (Denis Nosnitsin)

- 1. Introduction.

- 2. Historical overview.

- 3. Manuscript making.

- 3.1. Writing materials.

- 3.2. Writing.

- 3.3. Boards.

- 3.4. Leather.

- 3.5. Threads.

- 3.6. Decorations and miniatures.

- 4. Current situation.

- 4.1. The scribes.

- 4.2. Destruction, losses and hopes.

- Quoted bibliography.

Lǝggat Qirqos, Gulo Mäkäda district, East Tigray

(Denis Nosnitsin)

In the course of the cataloguing work of Ethio-SPaRe, the locality Ləg(g)at has been noticed as a site potentially important for the study of the local manuscript culture because the place name appeared in the colophons of some recent manuscripts[1]. Ləggat is locally well known mainly due to its church Ləggat Qirqos (/č̣erqos)[2]. The first visit of the Ethio-SPaRe team members[3] to the place happened in December 2012, when the project group visited the locality and the church returning from a trip to Zälambässa. To reach Ləggat, one has to drive a few kilometres from Zälambässa in the direction of ˁAddigrat on the main road, then turn southward and briefly continue on a rural road. The church Ləggat Qirqos stands on a rocky hill, from where a wide view opens over the terrain around[4]. The village Ləggat lies just below, nearby. The church is a modern structure[5]. A few other small churches are located near Ləggat Qirqos, such as ˁAddi Ṭäqäna/ Qäṭäna Maryam[6], Zәban Ḥoṣa Mikaˀel and Mažäna Yoḥannәs. The Eritrean border is only a couple of kilometres away; the famous church Gunaguna stands on the other side, also not far from the border, and many other ecclesiastic sites are scattered around. In December 2012, the aim of the Ethio-SPaRe team was to see the manuscript collection of Ləggat Qirqos. The collection turned inaccessible on that specific day[7], yet we were kindly received by mäˀlakä ḥәywät Dästa Gäbrämaryam, one of the local inhabitants and a prominent scribe (see below). He told us about the place and his occupation, showed his instruments and demonstrated how he works. The material collected during that short visit was later published by Magdalena Krzyzanowska in her 2015 article, presenting a few scribes from various localities Tigray[8]. In the next years, the scale of the scribal work at Ləggat gradually became clear to me. The village of scribes at Ləggat has been a significant centre of the local manuscript culture in the district of Gulo Mäkäda and beyond, largely overlooked before and definitely worth of further study. It is not an exaggeration to say that Ləggat (Qirqos) is one of the unique historical places of Tigray where the invaluable cultural heritage, both tangible and intangible, has been amassed and handed down from generation to generation.

I could visit Ləggat again only in March 2019[9], within the framework of the project Beta maṣāḥǝft: Manuscripts of Ethiopia and Eritrea, and met there only one scribe, the priest Mäbrahtom Dərar Wäldäqirqos. I made a short interview with him, and observed closely the process of writing. My further contacts with the scribes of Ləggat were interrupted due to the pandemic and the armed conflict that broke out between Tigray and the Federal Government of Ethiopia in November 2020.

The war severely affected Ləggat and entire area around it, and brought the community of the scribes to the brink of collapse. Following tragic news which I received from Ləggat in the late 2021 and in 2022 (see below), I arranged that two researchers from Adigrat University, Mr Hagos Gebremariam and Mr Amanuel Abrha[10], would go to Ləggat and make a brief survey of the scribal community’s condition and interview the available scribes on behalf of the project Beta maṣāḥǝft: Manuscript of Ethiopia and Eritrea[11]. Their visits took place in July 2022[12], and they could collect basic information about 11 scribes of Ləggat[13]. Here below follows their report, with some slight changes and additions, illustrated with images taken by them recently and by myself in the past years.

Fig. 1. Ləggat Qirqos, general view, 2019 (photo-credit: Ethio-SPaRe)

Fig. 2. Ləggat Qirqos, general view, 2019 (photo-credit: Ethio-SPaRe)

Fig. 3. Stone “throne” standing just outside the church compound (photo-credit: Ethio-SPaRe)

Fig. 4. A view of Zälambäsa and the church Zälambäsa Mädḥane ˁAläm from the brink of the Ləggat village, close to the main road, 2019 (photo-credit: Ethio-SPaRe)

Book-making tradition at Ləggat, Gulo Mäkäda district

(Amanuel Abrha, Hagos Gebremariam, Denis Nosnitsin)

1. Introduction

The subject of this report is the manuscript-making tradition that exists over many years in the village of Ləggat (ṭabiya Ḥaddis ˀAläm, Gulo Mäkäda wäräda, East Tigray), where most of the grown-up men are engaged in the production of parchment manuscripts. The information about the familiar and professional background of the scribes, as well as materials and techniques of bookmaking they use, was collected in the course of a visit to Ləggat which took place in July 2022. The report below is based on interviews with the scribes and encompasses a short historical overview, a brief survey of the local manuscript making tradition, a register of the scribes of Ləggat, and a brief description of the current situation.

2. Historical overview

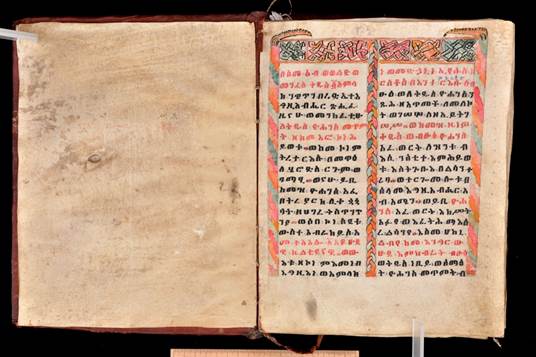

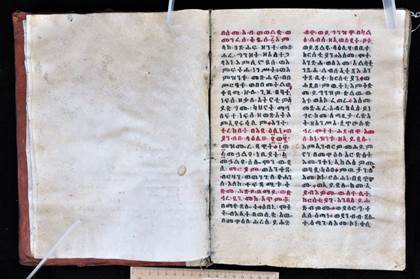

The local tradition presents the history of Ləggat as follows. The church Ləggat Qirqos (č̣erqos) is believed to be one of the ancient churches of Gulo Mäkäda. According to the community, the church was destroyed in the 10th century by Queen Yodit/Gudit and again in the 16th century by the troops of Aḥmed Graññ[14]. The history of the scribes is reported to have started during the time of Emperor Yoḥannәs IV (r. 1872–89). A son of the local man called Bilata[15] Gallo and a member of the administration of Emperor Yoḥannәs, ˀabba Wäldäqirqos (Wäldäč̣erqos) got a chance to learn the scribal skills in ˀAksum and returned back to his home village Ləggat. With the help of his father Bilata Gallo, ˀabba Wäldäqirqos established a scribal centre at Ləggat. Many young men came there to learn scribing. His son, the late Dərar Wäldäqirqos was one of the well-known scribes in Tigray (see fig. 5).

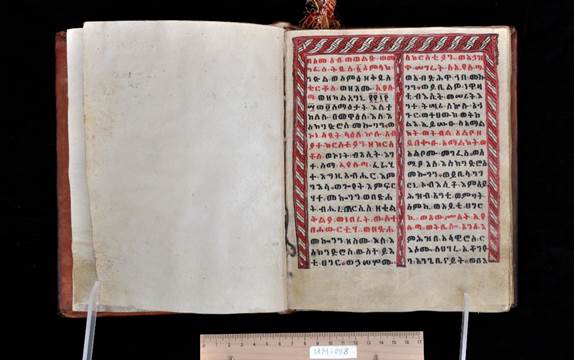

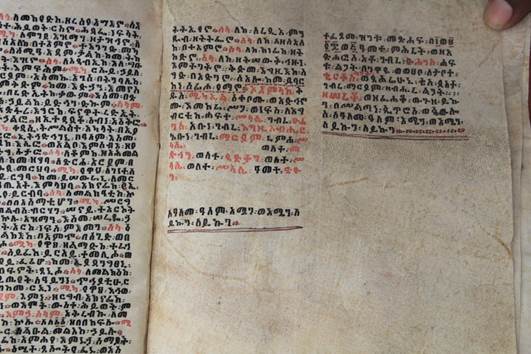

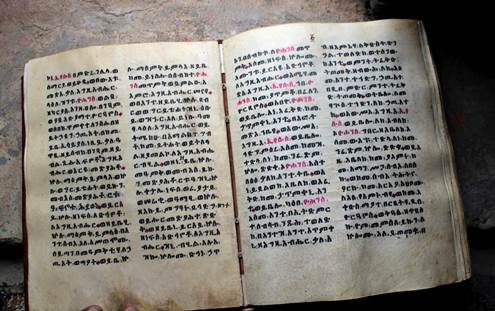

Fig. 5. Ms. Däbrä Maˁṣo Yoḥannәs MY-023, collection of texts about John the Baptist, dated 1969, written by Dərar Wäldäqirqos (photo-credit: Ethio-SPaRe)

A son of Dərar Wäldäqirqos, the priest Mäbrahtom Dərar is now active in Ləggat as a scribe. It is told that there were up to 63 scribes in Ləggat during some periods in the past. The scribes of Ləggat claim that more than 35,000 parchment books have been produced in Ləggat for the neighbouring areas and other places in Tigray and Eritrea; Tigrayans from the diaspora used to order in Ləggat books for Ethiopian churches in the US, England, Greece and Canada[16].

3. Manuscript making

The scribes of Ləggat share similar manuscript-making techniques. They use nearly the same materials; their methods of preparing parchment, inks, pens etc., and their binding techniques do not differ much. They have been taught by the same teachers who originate from the same locality.

The scribes say that they know how to carry out all stages of book production, but today they prefer to buy some of the materials and do not prepare them with their own hands. They usually work independently from each other, at their houses. With the exceptions of some stages of the manuscript production (e.g. parchmenting) joint manuscript-making projects are not common.

3.1. Writing materials

3.1.1. Parchment

All scribes of Ləggat use parchment as writing support, and the techniques of parchment making used by them is similar. Parchment is prepared from such domestic animals such as goats and sheep, and cows. The scribes prefer to use goatskins because of its better quality, while cow skins are usually preferred for large books and for the production of leather cases used for keeping and carrying the books. The scribes can prepare parchment by themselves, in which case they select and purchase from “skin stores” (the people who buy, collect and store skins of slaughtered domestic animals, and later sell them).

Fig. 6. Ready parchment kept in rolls (photo-credit: Ethio-SPaRe)

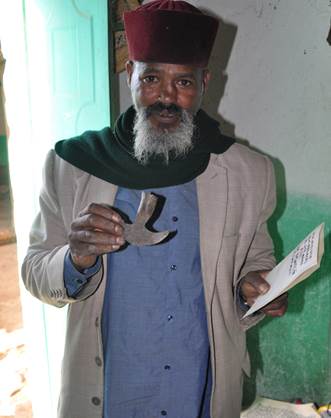

Fig. 7. Frame with a skin stretched (iron rods inserted into the edges of the skin) (photo-credit: Hagos Gebremariam)

Fig. 8. Frame for stretching skins (with iron rods inserted), adze-like instrument used for scraping (photo-credit: Hagos Gebremariam)

Fig. 9. Frame for stretching skins (with inserted iron rods), adze-like instrument used for scraping the hair-side (photo-credit: Hagos Gebremariam)

Fig. 10. Frame for stretching skins (with inserted iron rods), adze-like instrument used for scraping the hair-side (photo-credit: Hagos Gebremariam)

Fig. 11. Priest Mäbrahtom Dәrar holding lunette-like instrument (the handle missing), for scraping the flesh side of the skin (photo-credit: Ethio-SPaRe)

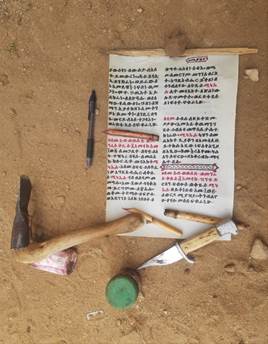

3.1.2. Pens

The pens used by the scribes are made of the locally available reed plant šamba qo[17]. Some scribes indicated that they get it from the nearby place Sämaz[18]. Each scribe collects reed stems from his surroundings, cuts them into sections and dry; he carves and shapes the pen end, and finally cuts the pen nib with a sharp knife. The scribes use different pens for inks of different colours.

Fig. 12. Two pens for red, one pen for black inks; adze-like instrument, container for ink, knife, parchment with writing (photo-credit: Hagos Gebremariam)

Fig. 13. Scraping of the pen with a razor blade (photo-credit: Hagos Gebremariam)

Fig. 14. Dästa Gäbrämaryam scraping the pen with a razor blade (photo-credit: Ethio-SPaRe)

3.1.3. Ink

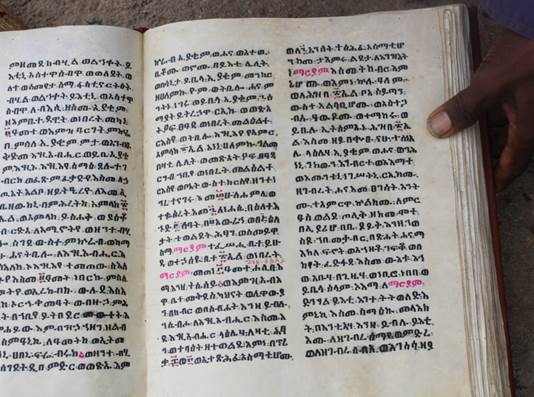

The scribes of Ləggat use for writing the inks of only two colours, black and red. The scribes prepare the black ink by themselves while purchasing the red ink, industrially produced, from the nearest markets.

Fig. 15. Container with black ink, scissors, awl, pen, stone or piece of ceramics for polishing the parchment surface (photo-credit: Hagos Gebremariam)

Fig. 16. Two pens for red, one pen for black inks; container for red ink (photo-credit: Hagos Gebremariam)

Fig. 17. Containers for red and black inks of the scribe Dästa Gäbrämaryam (photo-credit: Ethio-SPaRe)

To prepare inks, all scribes of Ləggat know and use the same basic ingredients, proportions and more or less the same methods. First, they roast barley, one of the main local cereal crops, until it becomes charcoal. Having added water, they place the roasted barley in a well-sealed vessel for several days. After a few days of reaction of the roasted barley with the water, they extract the water. Second, they roast leaves of tahsos[19] and leaves of qonṭäfṭäfä[20], both locally available plants, and grind them to dust mixing together. They add water from the roasted barley solution, a kind of dough emerges from this operation which they knead. When they are kneading the mixture, they add to it the substance called ˁәndadiˁ, a kind of resin that can be extracted or collected from the plant č̣äˁa[21], that functions as binder. This helps to enhance the brightness and the colour of the ink. A half-dry chunk of “the ink dough” can be kept over time, the scribe takes bit by bit from it, to prepare fluid ink when needed.

Although roasted barley is the basic ingredient for the preparation of the black ink, also the lamp black and charcoal were and are still used, and can replace the roasted barley, the other procedures remaining essentially the same.

According to Mäbrahtom Dərar, his grandfather who was one of the earliest scribes at Ləggat could prepare red inks from locally available plants but now Mäbrahtom does not remember the ingredients and preparation techniques. All scribes at Ləggat do not prepare red inks but buy them from their local markets. Such inks are available at construction material shops of the nearest towns Zälambäsa, Faṣi and ˁAddigrat. The scribes of Ləggat frequently add ˁәndadiˁ-resin to these inks, to enhance their quality (colour and durability).

Fig. 18. ˁƎndadiˁ-resin on a tree (photo-credit: Hagos Gebremariam)

Fig. 19. ˁƎndadiˁ-resin on a tree (photo-credit: Hagos Gebremariam)

o

Fig. 20. Trees from which ˁәndadiˁ can be extracted (photo-credit: Hagos Gebremariam)

Fig. 21. ˁƎndadiˁ producing tree (photo-credit: Hagos Gebremariam)

Fig. 22. ˁƎndadiˁ producing tree (photo-credit: Hagos Gebremariam)

Fig. 23. ˁƎndadiˁ producing tree (photo-credit: Hagos Gebremariam)

Fig. 24. ˁƎndadiˁ-resin (photo-credit: Hagos Gebremariam)

Fig. 25. ˁƎndadiˁ-resin (photo-credit: Hagos Gebremariam)

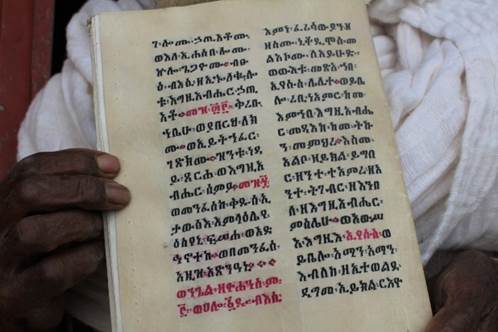

3.2. Writing

The scribes tend to rather long work times, working on average eight or nine hours a day, or even more if they have to comply with an urgent commission or to meet a deadline. The slowest copying speed is three medium-size pages a day, the quickest scribe can copy up to six medium-size pages a day (the average is four to five pages). All scribes check their texts after the completion of the copying, before the book is submitted to its commissioner. They add omissions at the appropriate places (also with the help of special signs); they commonly scrape out wrong words or letters with a razor blade and insert correct readings over erasures.

3.3. Boards

The wood usually used for boards of the bindings is ˀawḥi[22], because it is light and easy for carving. Some scribes use qolqwal[23] or ˀawlәˁ[24], formerly also eucalyptus was used. Nowadays there is wood that is lighter and easier to carve than ˀawḥi and eucalyptus, available at construction materials shops in the towns around (esp. Zälambäsa and Faṣi). The scribes mostly purchase this wood and make boards out of it.

3.4. Leather

All scribes of the area purchase ready leather (made of sheep or goatskins) either from the vicinity of Däbrä Dammo or from the local markets at ˁAddigrat. The manuscript-making tradition exists in these places. The local scribes prepare leather for their books, and also for selling it at the local markets of ˁAddigrat and Faṣi towns, where the scribes of Ləggat can find and buy it.

3.5. Threads

All scribes of Ləggat use threads made of twisted parchment strips[25].

Fig. 26. Instruments and materials of mälˀakä ḥәywät Dästa Gäbrämaryam: five tooling instruments, awl, scissors, metal ruler, pens; leaves of parchment, piece of leather for bindings (under the objects) and in a roll (left); narrow strip of parchment for making threads in the middle (photo-credit: Ethio-SPaRe)

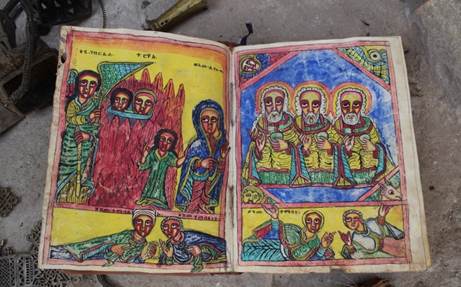

3.6. Decorations and miniatures

Most manuscripts produced by the scribes of Ləggat have neither miniatures nor other decorations. Mäbrahtom Dərar knows how to paint miniatures, and also ḥaläqa Mäḥari ˀAsfәha (see below) sometimes paints miniatures in his books. As to the ḥaräg-ornamental bands, only Mäbrahtom Dərar, Mäḥari ˀAsfәha and Fəssəḥa Gərmay (see below) can paint them. If necessary, the scribes involve professional painters from other places.

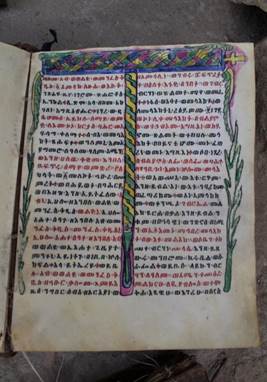

Fig. 27. Sample of miniature art from Ləggat (photo-credit: Hagos Gebremariam)

Fig. 28. Sample of ḥaräg-ornamental band from Ləggat, by an unnamed painter, the text copied possibly by Dästa Gäbrämaryam, see below (photo-credit: Hagos Gebremariam)

4. Current situation

4.1. The scribes

For July/August 2022, there were 11 scribers living in Ləggat, all being members of the “Association of Ligat Scribes” (ማሕበር ፀሃፍያነ ብራና ዘብሄረ ልጋት). In addition, they run a scribal school attended by a number of boys. All scribes are natives of Ləggat, in part connected to each other through family links.

Here below is a list of the scribes who were interviewed at Ləggat in July 2022, with selected information they provided about themselves and their work. All the scribes spend most of their time at Ləggat, though some lived for a while at other places or even abroad. For all of them the scribing is not their only occupation; they all work also as farmers and serve in the church (the youngest has not finished school yet). No one of them sells their manuscripts at the book market of ˀAksum, all work exclusively upon commission. The scribes do not produce manuscripts if there are no commissioners.

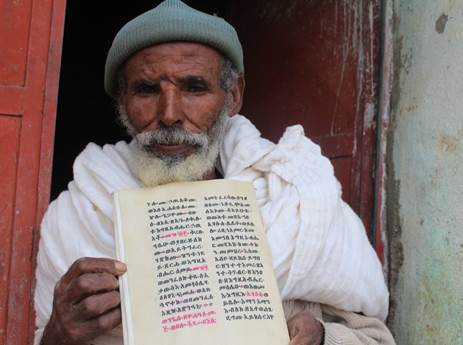

1. Mälˀakä mәḥrät Muluˀaläm Gäbrämaryam (59) (†). He started to learn the scribal profession at Ləggat from his brother mälˀakä ḥәywät Dästa Gäbrämaryam, at the age of 16, and accomplished his learning in two years. He copied, according to his own words, at least 122 books including psalters and chant books[26].

Fig. 29. Mälˀakä mәḥrät Muluˀaläm Gäbrämaryam (photo-credit: Amanuel Abrha)

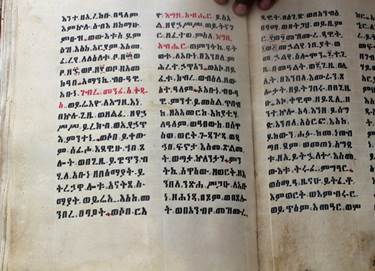

Fig. 30. Sample of the handwriting of mälˀakä mәḥrät Muluˀaläm Gäbrämaryam (photo-credit: Amanuel Abrha)

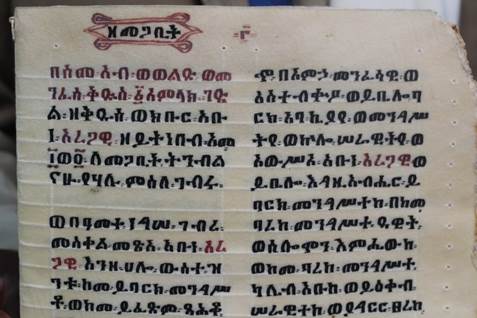

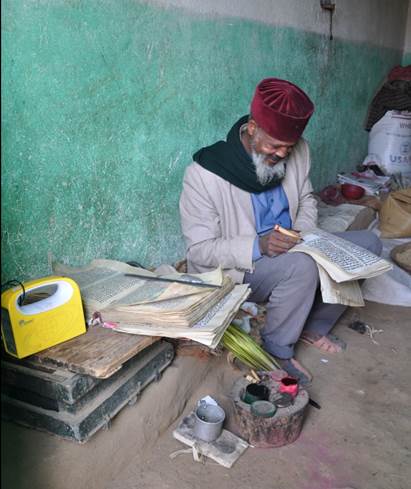

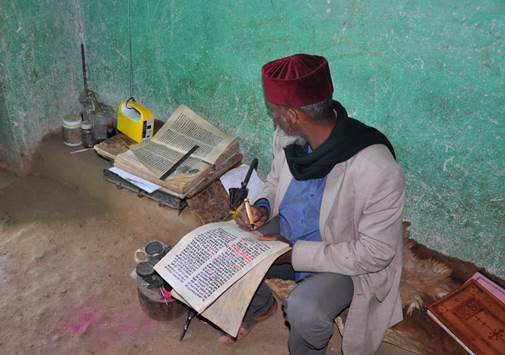

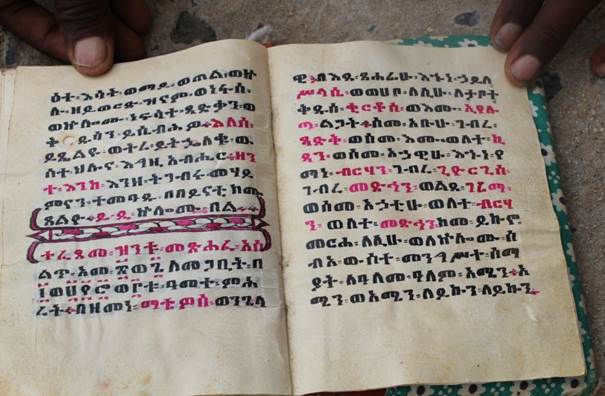

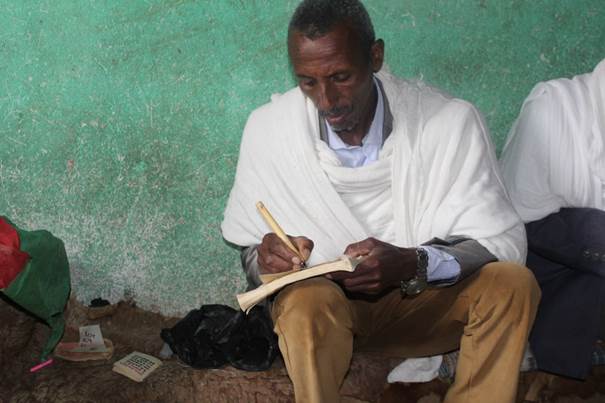

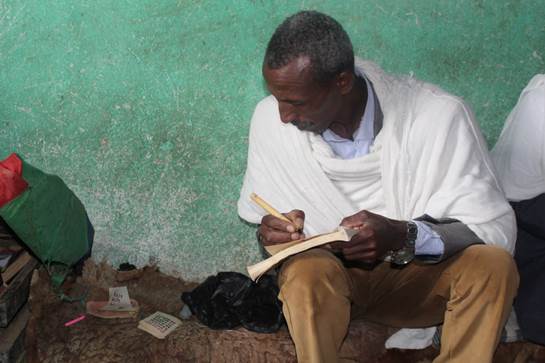

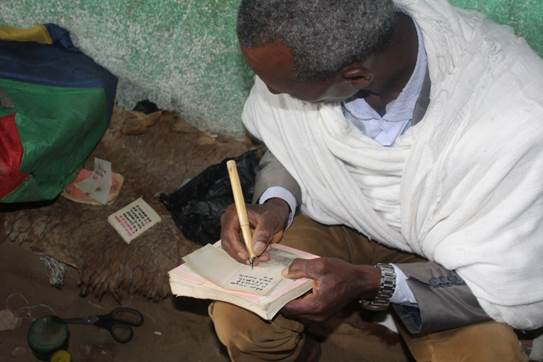

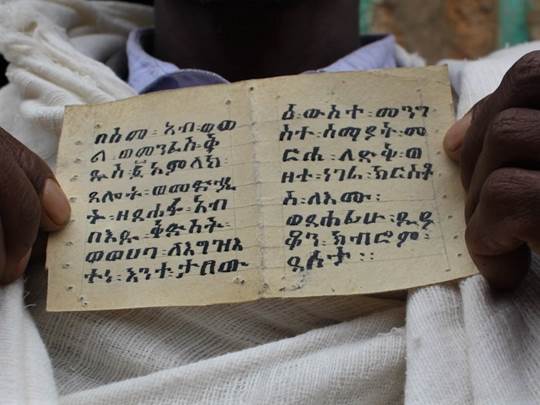

2. Mälˀakä hәywät Dästa Gäbrämaryam (77) (†). He started to learn the scribal profession at Ləggat from his neighbour ˀabba Wäldäqirqos Gallo, at the age of 16, and accomplished his learning in one year and a half. He copied, according to his own words, 154 manuscripts, including six psalters and chant books. He knew how to paint miniatures and ḥaräg-ornamental bands[27].

Fig. 31. Mälˀakä ḥәywät Dästa Gäbrämaryam writing (photo-credit: Ethio-SPaRe)

Fig. 32. Mälˀakä ḥәywät Dästa Gäbrämaryam writing (photo-credit: Ethio-SPaRe)

Fig. 33. Mälˀakä ḥәywät Dästa Gäbrämaryam burnishing the surface of a parchment leaf before writing (photo-credit: Ethio-SPaRe)

Fig. 34. Sample of writing of mälˀakä ḥәywät Dästa Gäbrämaryam, Ms. ˁUra Qirqos, UM-008, Vita and Miracles of St. Cyricus, dated 1976 (photo-credit: Ethio-SPaRe)

Fig. 35. Sample of writing of mälˀakä ḥәywät Dästa Gäbrämaryam (photo-credit: Hagos Gebremariam)

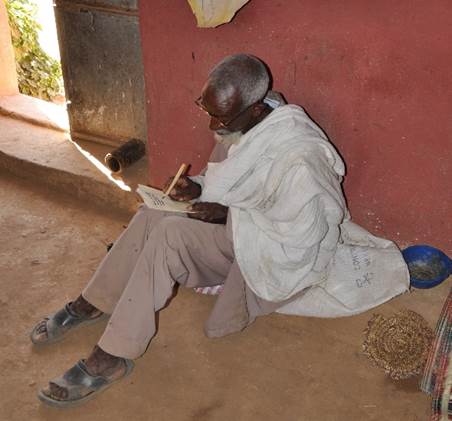

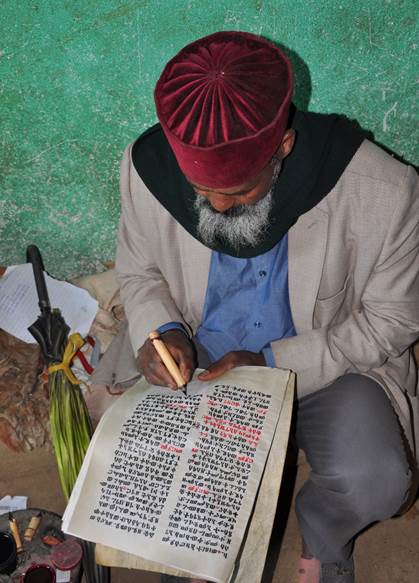

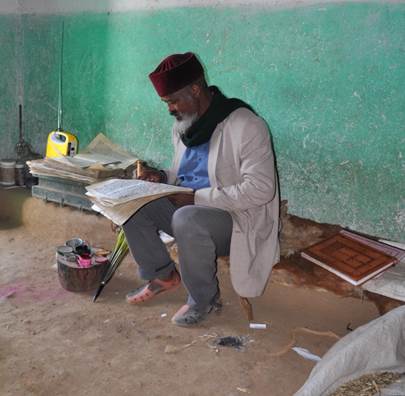

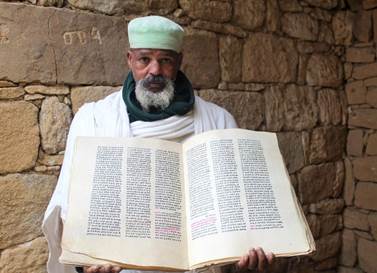

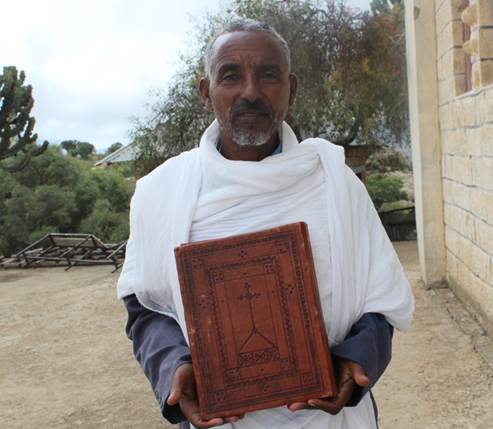

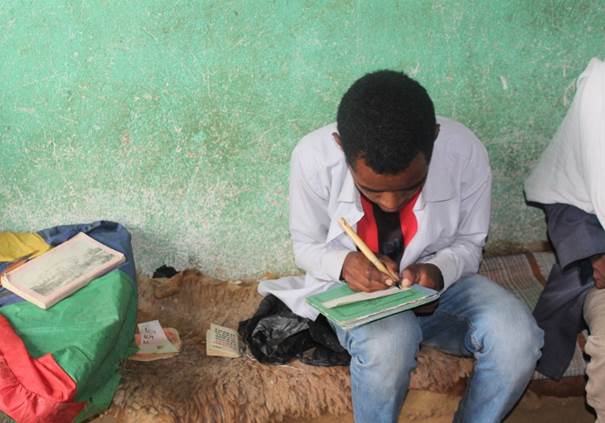

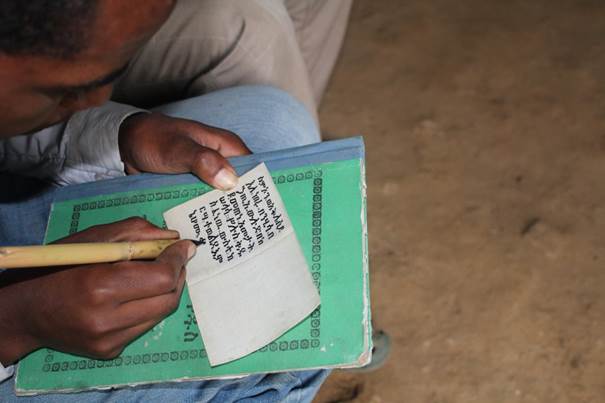

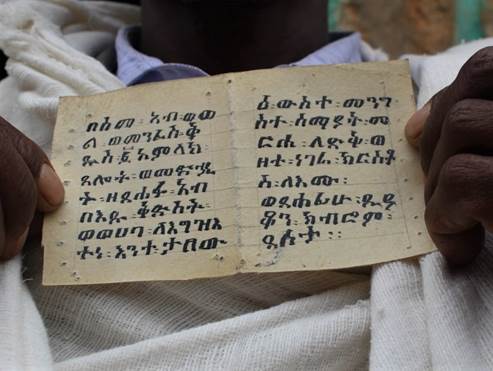

3. Priest Mäbrahtom Dərar (53). He started to learn the scribal profession at Ləggat at the age of 10, from his father Dərar Wäldäqirqos, and became an accomplished and skilful scribe at the age of 20. He copied, according to his own words, at least 100 manuscripts, writing three or four books per year. He can paint miniatures and ḥaräg-ornamental bands.

Fig. 36. Mäbrahtom Dərar at work, copying “Miracles of Mary” for the church Säglat Maryam from the exemplar, dated 1963, that belonged to his father Dərar Wäldäqirqos (photo-credit: Ethio-SPaRe)

Fig. 37. Mäbrahtom Dərar at work (cp. fig. 36), writing in a quire placed at his lap (photo-credit: Ethio-SPaRe)

Fig. 38. Mäbrahtom Dərar at work (cp. fig. 36) (photo-credit: Ethio-SPaRe)

Fig. 39. Mäbrahtom Dərar at work (cp. fig. 36), looking at his exemplar (photo-credit: Ethio-SPaRe)

Fig. 40. Mäbrahtom Dərar at work (cp. fig. 36), dipping the pen for red into red ink to write a rubricated passage, holding the pen for black in his teeth (photo-credit: Ethio-SPaRe)

Fig. 41. Mäbrahtom Dərar and his book (photo-credit: Amanuel Abrha)

4. Priest Hayläsəllase Gäbräṣadəq (66). He started to learn the scribal profession at Ləggat at the age of 14, from märigeta Dərar Wäldäqirqos, and accomplished his learning in four years. He copied, according to his own words, 84 manuscripts, including a few psalters and chant books.

Fig. 42. Sample of handwriting of Hayläsəllase Gäbräṣadəq (photo-credit: Amanuel Abrha)

Fig. 43. Sample of handwriting of Hayläsəllase Gäbräṣadəq, Ms. Däbrä Maˁṣo Yoḥannәs, MY-007, Book of the Funeral Ritual, dated 1978 (photo-credit: Ethio-SPaRe)

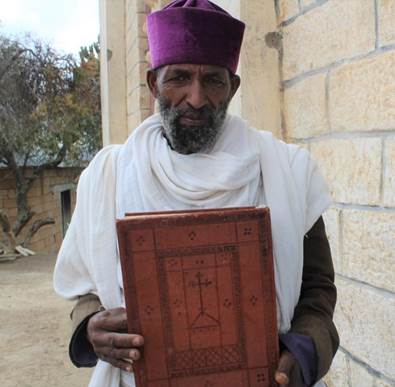

5. Priest Fəssəḥa Gərmay (73). He started to learn the scribal profession at Ləggat at the age of 25, from Dästa Gäbrämaryam, and accomplished his learning in two years. He copied, according to his own words, 48 manuscripts.

Fig. 44. Fəssəḥa Gərmay with a text quire written by him (photo-credit: Amanuel Abrha)

Fig. 45. Sample of handwriting of Fəssəḥa Gərmay (photo-credit: Amanuel Abrha)

6. Mälˀakä ṣäḥay Täsfaˀaläm Mäḥari (58). He started to learn the scribal profession at Ləggat at the age of 16, from mälakä ḥәywät Dästa Gäbrämaryam, and accomplished his learning in four years. He copied, according to his own words, 46 manuscripts.

Fig. 46. Mälˀakä ṣäḥay Täsfaˀaläm Mäḥari (photo-credit: Hagos Gebremariam)

Fig. 47. Sample of handwriting of mälˀakä ṣäḥay Täsfaˀaläm Mäḥari (photo-credit: Amanuel Abrha)

7. Ḥaläqa Mäḥari ˀAsfәha (60). He started to learn the scribal profession at Ləggat at the age of 16, from Dərar Wäldäqirqos, and accomplished his learning in four years. He copied, according to his own words, 74 manuscripts, a couple of psalters and chant books being among them. He paints ḥaräg-ornamental bands in his books by himself, and sometimes also paint miniatures.

Fig. 48. Ḥaläqa Mäḥari ˀAsfәha (photo-credit: Amanuel Abrha)

Fig. 49. Sample of writing of ḥaläqa Mäḥari ˀAsfәha (photo-credit: Amanuel Abrha)

8. Deacon Yämanä Gäbräṣadəq (60). He started to learn the scribal profession at Ləggat at the age of 15, from Dästa Gäbrämaryam and his brother Hayläsəllase Gäbräṣadəq, and accomplished his learning in five years. He copied 11 manuscripts.

Fig. 50. Yämanä Gäbräṣadəq with his book (photo-credit: Amanuel Abrha)

Fig. 51. Sample of writing of Yämanä Gäbräṣadəq (photo-credit: Amanuel Abrha)

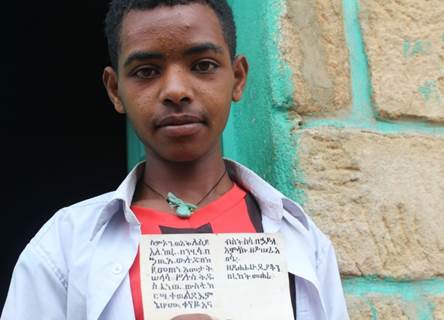

9. Deacon Bäräkät Mäḥari (16). He started to learn the scribal profession at the age of 14, and he is still learning from his father Mäḥari ˀAsfәha (see above). He has not copied any manuscripts in full yet, and uses his father’s parchment for writing.

Fig. 52. Bäräkät Mäḥari (photo-credit: Amanuel Abrha)

Fig. 53. Bäräkät Mäḥari at work (photo-credit: Amanuel Abrha)

Fig. 54. Bäräkät Mäḥari at work (photo-credit: Amanuel Abrha)

Fig. 55. Bäräkät Mäḥari at work (photo-credit: Amanuel Abrha)

Fig. 56. Sample of handwriting of Bäräkät Mäḥari (photo-credit: Amanuel Abrha)

10. Deacon Kəbrom Dästa (51). He started to learn the scribal profession at the age of 21 from mälˀakä ḥәywät Dästa Gäbrämaryam and Yämanä Gäbräṣadəq, and accomplished his learning in six years. He copied, according to his own words, 11 small-size manuscripts.

Fig. 57. Kəbrom Dästa and a sample of his writing (photo-credit: Amanuel Abrha)

Fig. 58. Kəbrom Dästa at work (photo-credit: Amanuel Abrha)

Fig. 59. Kəbrom Dästa at work, looking at his exemplar (photo-credit: Amanuel Abrha)

Fig. 60. Kəbrom Dästa at work, looking at his exemplar (photo-credit: Amanuel Abrha)

Fig. 61. Sample of handwriting of Kəbrom Dästa (photo-credit: Amanuel Abrha)

11. Deacon Nägasi Fəssəḥa. He was not in Ləggat at the time of the visit, and it was not possible to collect information about him.

4.2. Destruction, losses and hopes

Now, the scribal community of Ləggat struggles for survival. According to the scribes, their materials were looted and destroyed by the Eritrean troops in the period from November 2020 to June 2021. The church Ləggat Qirqos, with its manuscript library, was also looted and badly damaged[28]. No one commissioned any books over many months: this was a serious blow to the economic situation of the scribes’ housholds. Mälˀakä ḥәywät Dästa Gäbrämaryam, the leading scribe of the commmunity, died because of the lack of medicine and medical help in December 2022. Around the same time, another prominent scribe, mälˀakä mәḥrät Muluˀaläm Gäbrämaryam, who was also the head of Gulo Mäkäda district church administration, died in a bicycle incident near his village. Some of the scribes left Ləggat, those who remain are deeply frustrated. They love their work and they still want to copy books and teach the scribal profession to the young people. However, their situation is extremely precarious. They want to reactivate the “Association” and resume scribing work at Ləggat. Discussions as to how to proceed are underway, also the members of the Adigrat University are involved. There are plans to restart their traditional work and to help in producing copies of books to substitute for the burnt and looted ones in the neighbouring churches, but the current situation in the region is still not conducive enough for that.

Fig. 62. Mr Amanuel Abraha (above left), scribes of Ləggat and their disciples, July 2022 (photo-credit: Hagos Gebremariam)

Fig. 63. Scribes of Ləggat, July 2022 (photo-credit: Hagos Gebremariam)

Fig. 64. Community of Ləggat at assembly, July 2022, the church building with damaged roof and walls in the background (photo-credit: Hagos Gebremariam)

Fig. 65. Community of Ləggat at an assembly, July 2022 (photo-credit: Hagos Gebremariam)

Quoted bibliography

Conti Rossini, C. 1901. “L’evangelo d’oro di Dabra Libānos”. Rendiconti della Reale Accademia dei Lincei, Classe di scienze morali, storiche e filologiche Serie quinta, 10, pp. 177–219.

Kane, T.L. 1990. Amharic–English Dictionary, Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

Kane, T.L. 2000. Tigrinya-English Dictionary, Springfield, VA: Dunwoody Press.

Krzyżanowska, M. 2015. “Contemporary Scribes of Eastern Tigray (Ethiopia)”. Rocznik Orientalistyczny/Yearbook of Oriental Studies. The Committee of Oriental Studies of the Polish Academy of Sciences and The Publishing House ELIPSA, 68-2, pp. 73–101 [https://journals.pan.pl/dlibra/publication/95526/edition/82296/content].

Nosnitsin, D. 2013. Churches and Monasteries of Tǝgray: A Survey of Manuscript Collections. Supplement to Aethiopica 1. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

Nosnitsin, D. 2020 “Christian Manuscript Culture of the Ethiopian-Eritrean Highlands: Some Analytical Insights”. In A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, ed. by Samantha Kelly, Leiden–Boston, MA: Brill, pp. 282–321.

[https://brill.com/view/book/edcoll/9789004419582/BP000024.xml].

[1] Cp. a reference to “Ləgat” in Nosnitsin 2013, and the same spelling in Krzyżanowska 2015 (see below). The correct spelling of the name seems to be rather Ləggat (with gemination), following the local pronunciation which however has not been fully ascertained. It appears to be an old place name. An explanation proposed by the local tradition is that the name Ləggat is somehow connected to the Tigrigna word lägaˁ (pl. lägaˁat), “cow close to calving; colostrum” (Kane 2000:142a), I thank Mr Hagos Gebremariam for this information.

[2] Sometimes also referred to as Zälambäsa Qirqos/Cherqos.

[3] Denis Nosnitsin and Magdalena Krzyzanowska, accompanied by the field assistant Fәṣṣum Gäbru (the church administration of East Tigray).

[4] Wäräda Gulo Mäkäda, ṭabiya Ḥaddis ˀAläm, qušät Lәggat, within the modern administrative division. The geographical coordinates of the site are 14.477547, 39.393307.

[5] The presence of of pre-medieval (Aksumite?) stone structures inside the church compound has been reported to me, and also some some other potentially rich and still unstudied archaeological sites in the vicinity (I thank Mr Amanuel Abraha for this information).

[6] Probably the same place as that mentioned in one of the recent land documents encompased by the “Golden Gospels book” of Ham (Conti Rossini 1901:11, no. 2).

[7] According to the information gathered later, the collection of Ləggat Qirqos is not large and in its present state encompasses some 15 to 20 books. However, one manuscript, the Acts of Libanos, was identified as copied by the most prolific local scribe Zäwäldä Maryam who was active in the area in the first half/around the middle of the 18th century (see Nosnitsin 2013, index; see also the database of the project Beta maṣāḥǝft: Manuscripts of Ethiopia and Eritrea, https://betamasaheft.eu/persons/PRS12076ZawaldaMaryam/main [accessed 04.05.2023]).

[8] Krzyżanowska 2015; this information on Ləggat and his scribes and their backgrounds as well as on other scribes of Tigray appears especially valuable today, after the ten-year lapse.

[9] Together with Ms Magdalena Krzyzanowska (research fellow, HLCEES), and accompanied by Mr Hagos Gebremariam (Adigrat University, see below).

[10] Mr Hagos Gebremariam MA, lecturer and research assistant at the Department of Sociology, and Mr Amanuel Abrha MA, lecturer and research assistant at the Department of Archaeology and Heritage Management (Adigrat University).

[11] The long-term project “Beta maṣāḥəft: Manuscripts of Ethiopia and Eritrea,” funded by the Academy of Sciences and Humanities in Hamburg (https://www.betamasaheft.uni-hamburg.de/). I thank the head of the project, Prof. Alessandro Bausi, for his support of the undertaking.

[12] At this point, both Hagos and Amanuel should be cordially thanked for carrying out the undertaking in the extremely complicated situation of the Tigray conflict, for the sake of research, love to their own culture and preservtion of the cultural heritage of Tigray.

[13] Cp. seven scribes who were mentioned in 2012, see Krzyżanowska 2015:77 (the report below shows a few minor variations in personal names, such as Gәrma vs Gәrmay [see below], or separate vs connected parts of the compound personal names).

[14] The church was destroyed and became a camp for Eritrean troops also during the 1998-2000 Ethio-Eritrean border conflict. Again, Ləggat Qirqos was heavily hit by Eritrean troops in the recent Tigray war (see below).

[15] To be possibly interpreted as the court title blatta?(I thank Mr Amanuel Abrha for the hint). The older history of Ləggat as it was summarized by the community members has some puzzling moments.

[16] There are some indications that the history of the scribes at Ləggat predates the time of Yoḥannәs IV.

[17] Phragmites communis in Kane 2000:815a.

[18] Sämaz Maryam, see Nosnitsin 2013:44-49.

[19] Probably the same as tahsäs in Kane 2000:1218b, Dodonea viscosa.

[20] Probably the same as qwänṭäṭäfä in Kane 2000:1009a, Pterolobium lacerans.

[21] Kane 2000:2527a, Acacia spirocarpa.

[22] Kane 2000:1510a, Cordia africana.

[23] Kane 2000:891b, Euphorbia candelabra or Euphorbia abyssinica.

[24] In Amharic known as wäyra, “olive tree”, see Kane 1990:1559b.

[25] See Krzyżanowska 2015:88, and Nosnitsin 2020:296, footnote 60.

[26] The number of books mentioned by mälˀakä mәḥrät Muluˀaläm Gäbrämaryam (and by some other scribes below) is impressive, though not unrealistic, meaning some four (middle-size) books annualy over the span of 30 years, which is quite possible under good conditions (also see above, 3.2.).

[27] For information on this scribe, see Krzyżanowska 2015, and Nosnitsin 2020:311 (fig. 11.7).

[28] Reports about the heavy damage caused to the church “Zälambäsa Cherkos” (Ləggat Qirqos was referred to in the mass-media mostly this way) started to circulate in the social networks in January 2021, accompanied by a few pictures, showing, indeed, destruction inflicted on the church building and the church property. The incident was recorded also in “Situation Report EEPA HORN” No. 61, 20 January 2021 (https://www.eepa.be//wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Situation-Report-EEPA-Horn-No.-61-20-January-2021.pdf [accessed on 25.04.2023]).